Denny Memorial Hall

by Gordon Miller and John Fioravante

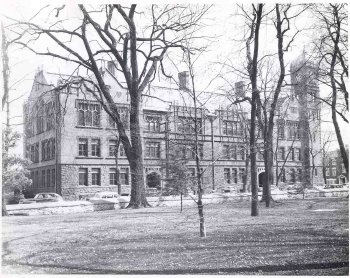

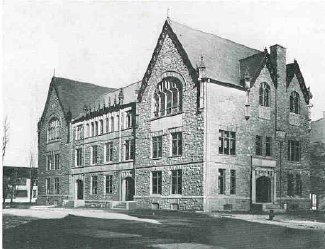

Denny Memorial Hall

Photo Courtesy of Dickinson

College Archives

Denny Memorial Hall

Photo Courtesy of Dickinson

College Archives

The origins of the Denny family trace back to Frederick and Eleanor Denny who immigrated to the American colonies from Ireland in 1681. They arrived in Salem, New Jersey and soon acquired property further north in Raccoon, Gloucester county. They had three sons, William (1699), Walter (1701) and John (1728) and moved west into Pennsylvania. Here they were considered Scotch Irish and settled first in Chester county. Then the two eldest sons pushed west to that part of Lancaster county simply called "beyond the Susquehanna" or the "North Valley" (present Cumberland Valley) in 1745. Before being killed in 1778 at the battle of Crooked Billet near Hatboro, Pennsylvania (north of Philadelphia) during the Revolutionary war, Walter Denny staked out land in West Pennsborough, but his farm in Lancaster remained the family's permanent home. The plantation to the west passed to his son John. Here, in the "wilderness," Walter Denny's brother, William raised his family to prominence on a South Middleton homestead near La Torte Spring and the future location of the town of Carlisle. He and his wife Agnes had three children; Martha, Walter and William Jr. A skilled cabinet maker and carpenter, William Denny Jr., was known as the first Coroner west of the Susquehanna and the contractor for the Brick Court House of 1765, which was destroyed by fire in 1845. His daughter Priscilla acquired lot number 29 on High Street from her husband Simon Boyd in 1814. Here a small log home had been run as a public house until 1758. This modest dwelling would stand until 1894, when it was replaced by a modern residence, then Denny Memorial Hall three years later.

Other notable Dennys were William

Jr.'s son Ebenezer and his wife Nancy Wilkins. This couple had twenty

children together--all the males prominent and influential citizens of

Pittsburgh. Ebenezer fought like his father in the Revolutionary war and

was in command of the Le Beuf expedition as well as the Commissary of purchases

during the War of 1812. He and his family relocated to Pittsburgh from

Carlisle and there became the town's first mayor and the Commissioner of

Allegheny county. Finally, Miss Mathilda Denny, granddaughter of

Ebenezer, sold the lot to Dickinson College for the sum of $100 with the

promise of a namesake memorial to the

Denny family.1

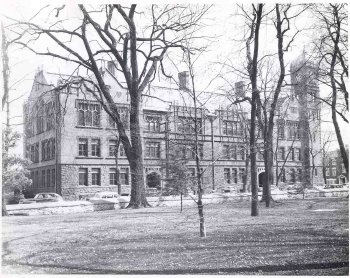

Lot number 29 on the north side of West High

Street, was home to a modest, log dwelling for nearly one hundred years.

During this time, the site of Denny Memorial Hall resembled not the ivied

temperance of academia, but the energy and fervor of a public house as

it was run as such from 1763 until a modern home replaced it in the late

1880s. In October, 1794, General Washington, in command of 7,000

men supplied with sixteen artillery pieces, agreed with Secretary Alexander

Hamilton that the contingent would rendezvous at the town of Carlisle before

continuing west to quell the Whiskey Rebellion. The Denny homestead

was then used as the General's headquarters and the ancient locust tree

still intact in the above photo, marked Washington's vantage point as he

surveyed the land to the west and the looming threat.2 A

Pennsylvania State Historical marker is on this spot today.

With the ascent to the Presidency of George Edward Reed, in 1889, Dickinson College entered a stage of unparalleled growth and change. The new President, being a former minister and an energetic and inspiring orator, attracted scores of students from the College's traditional pulling zones encompassed by the Philadelphia, New Jersey, Baltimore, East Baltimore and Central Pennsylvania Conferences of the Methodist Church. By the time of his retirement in 1912, Reed had quadrupled the student body and proportionately increased faculty positions. However, to accommodate this influx of students, the College required expansion. As a building housing recitation halls, offices and quarters for the Literary Societies, Denny Memorial Hall was the key project in the brightening Dickinson's future.

In order to fund this building, estimated to cost "no more than $25,000," the College, much like today, relied on the combination of the generosity of her alumni and bank loans. With this goal in mind, Dickinson issued a series of public advertisements and pamphlets to her alumni explaining the situation and what the old Alma Mater asked of her "beneficiaries."

"Why the Alumni should Interest Themselves..."

Fundraising rhetoric was interesting in itself. The College held that acquiring the Denny Property, "worth together nearly $16,000," was a primary concern as the proposed building was "an imperative necessity." Apparently, old recitation rooms in East and West College were overcrowded and becoming "hazardous" to the health of the students and the professors were "retarded and rendered less efficient," when forced to work under such deplorable conditions. Denny Memorial Hall would give the students "two elegant and commodious halls" for the Belles Lettres Literary Society and the Union Philosophical and "a fine room for Calisthenics for young women of the College and a complementary literary hall." Since attendance was "higher than ever, disaster would follow" if there was no change in the status quo.5

"What We Propose..."

| Dickinson

College expected every man and women "ever connected with the College"

to give assistance.

Reed and

the trustees asked for sums from $1,000 to $10 payable in installments

before November 1, 1895.

"As an alumnus

of the old college, will you not help her in her hour of need?

|

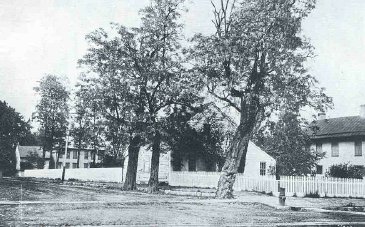

Sketch Courtesy of Dickinson College Archives |

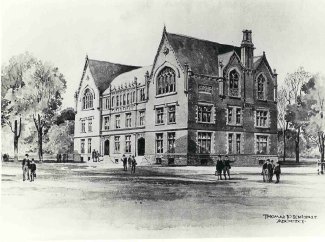

Denny Memorial Hall Realized

Denny Memorial Hall (1896)

Photo Courtesy of Dickinson

College Archives

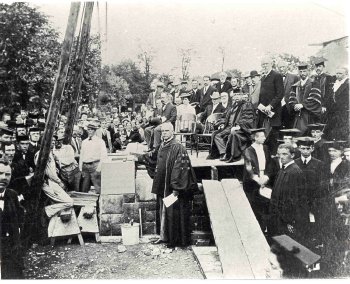

Ground was broken in a dedication ceremony involving the faculty,

trustees and President Reed on Thursday, April 25, 1895.7

A year later, Denny Memorial Hall was completed on June 8, 1896 at a cost

of nearly $40,000. The architect was Thomas P. Lonsdale of Philadelphia

and Mr. J. Herman Bosler of the class of 1854,

delivered the principal speech at the formal opening ceremony.8

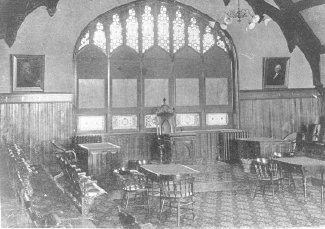

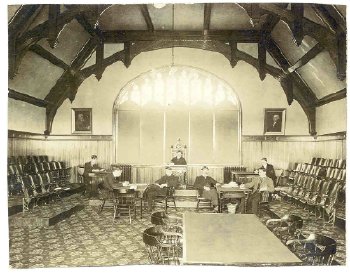

The highlights of the new building were the elaborate and awe-inspiring

third floor Literary Halls, each occupying one corner of Denny Hall with

the ladies' Literary Hall in between. In a Letter

to Dr. Charles F. Himes regarding the status of Denny Memorial Hall from

President Reed, the details and purpose of the building are further

discussed as is one last effort at fund raising to furnish such lovely

accommodations.

|

|

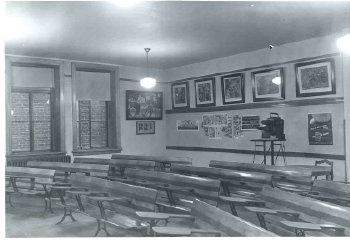

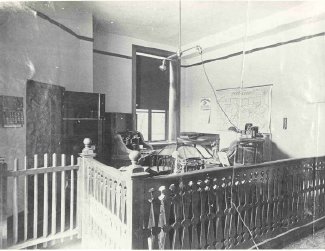

With their twin insignias of the red rose (Belles Lettres Society) and the white rose (Union Philosophical Society), Dickinson's two ancient Literary Societies, are responsible for red and white being the honorary colors of the College. They served to facilitate the 18th century art of rhetoric and public speaking and were the forum for the discussion of current events and literary masterpieces. The College at one time required membership in one of the societies and they were so prominent that their individual libraries exceeded that of the College's own collection. Often these rival societies engaged in competitive debates and vied at commencement to have more of their own members secure the most laurels. Much like the fraternities that would later begin to replace them, the Literary Societies were highly secretive and loyal to the brotherhood of the Society. They offered students solidarity in membership, a place to belong and complemented the individual's academic experience. The Belles Lettres Society and Union Philosophical occupied a vital role in the environs of Denny Memorial Hall as the building accommodated the societies in two vast, ornate halls which emphasized their dominance within student life. Soon after in 1896 the Harman Literary Society was established for the ladies on campus and was housed in the ample room bounded by the two men's societies. Unfortunately much of the earlier records of the Societies, especially those of the Union Philosophical, were lost in the disastrous fire of 1904. The legacy of the great literary societies can still be felt at Dickinson by common hour every Wednesday afternoon. Traditionally these afternoons were free of classes and reserved for convening of the Literary Societies and concurrent faculty meetings.10

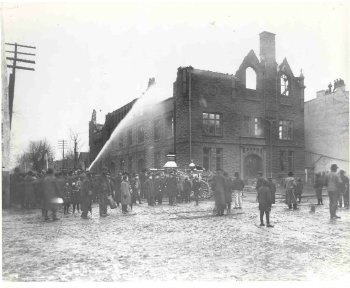

After only eight years of use, Denny Hall burned to the ground on March 3, 1904. The story behind the cause of the fire is that a freshman by the name of George Briner was sitting near the door in the third floor classroom and heard a knock and opened the door. Professor Sellers was there, saying something about smoke coming from Professor Landis' office.11 This was not too unusual due to Professor Landis' heavy addiction to cigars. The end result of the disaster produced more than the smell of cigar smoke, however, as the photographs below indicate.

|

|

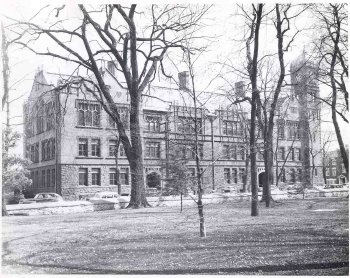

In June, 1904, the trustees authorized the reconstruction of Denny Hall, to be built of brownstone, and the second and third stories to be constructed of dark colored Ohio brick with brownstone trimmings. This masonry distinction would cause the building stand out against the traditional gray limestone of the other campus buildings but would complement the appearance of the newer Bosler Memorial Library completed in June, 1886. The "new" Denny consisted of eighteen classrooms and twenty faculty offices. The school hired architect, Miller I. Kast of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania for $62,964,12 and the hired contractor for both Dennys was A. N. Brindle. Also in the reconstruction, was the addition of a bell tower, named the Lenore Allison Tower, which was funded by a $2,500 gift.13

Although the trustees permitted the reconstruction of Denny Hall, the school was in need of money, as Dickinson had been undergoing an extensive building program to accommodate greater enrollment. With other projects already in progress, the College found itself in a financial crisis as it had limited means to execute its ambitious building program. This money came as a gift of $50,000 14 from Andrew Carnegie -- the single largest monetary gift the College had ever received. However, it was not used toward Denny Hall, but for another building that was also under construction--Conway Hall. But this gift now gave the school the additional resources to spare in order to go through with the reconstruction. Denny II was completed in 1905 at a final cost of $62,393.15 For the first 25 years the east side of Denny looked out over gardens and downtown Carlisle, until the Scott Building on high street blocked the light and view. The administrative offices were located in Denny until the 1920s after which they were relocated to Old West following the completion of major renovations there. Moreover, Denny housed the College Bookstore, biology labs and classrooms, located at the North end of the building, and the Mathematics department until the 1930's.

For the next seventy-nine years Denny remained as it was built in 1905, with no major improvements. There are a few notable exceptions however. First was the electrification of the clock and bell tower system for $1,150. The other was the the plan in 1959 to make a "theatre," for the Mermaid's Players, out of the vast Belles Lettres Literary Hall on the 3rd floor. A theater was created and housed the organization until the completion of Mathers Theatre in the Holland Union Building in 1964. In 1954, however, a survey was done on the condition of Denny Hall that valued it at $335,000. The surveyor also gave Denny a poor adequacy rating describing the building as cut off from light on the east by business building, difficult to ventilate, not fireproof, costly to maintain and rated obsolete. Despite this damning survey changes would not come for thirty years.

(Denny Rebuilding Account information)

President Reed laying the cornerstone (1904) for the

reconstruction of the new Denny Hall, after the fire

Photograph courtesy of the Dickinson

College Archives

|

|

|

|

|

It was not until 1984, when the decision was made to undergo a major renovation of Denny Hall, now desperately in need of modernization. The cost of the renovation was approximately $2.5 - 2.6 million, most of this, however, was covered by a government bond issue.16 According to the College student newspaper, Denny, though it happened to be in the worst condition, "was the last academic building to be renovated on campus ... because it was so far from the College's HUB."17 Complete renovation presented the College with a very large problem, however. The College needed to find somewhere to put all the displaced classes and offices which were a significant portion of the total space available on the entire campus. To solve this new dilemma, the College leased an old elementary school, Stevens, located about six blocks to the north of Dickinson on Franklin Street. This now became the farthest building from campus. Although the school now had a building to accommodate all the displaced classes, it had been built some years before for a very different kind of student and, according to the yearbook for 1984,"had leaky roofs, no air conditioning and silly coatrooms in the back of each class."18

Back at the main campus, the entire Denny Hall building was gutted and re-done. The exterior was cleaned and refurbished, energy efficient windows were installed, and window sills and trim were newly repainted.

See a photographic account of the Denny Renovations.

Work being done on the outside of Denny, 1984.

Photograph courtesy of Dickinson

College Archives

On the interior, the woodwork and doors were stripped of the many layers of paint that had accumulated over the years and were restored to the original yellow-pine finish. Cement now replaced the creaky wooden floors in the hallways and stairwells, and carpeting was laid throughout the building. The basement plans included a computer terminal room and a small faculty student lounge. Along with the restoration came the installation of a central air conditioner. The entrance doors were also replaced so they would now open outwards, a significant improvement in fire safety for the hundreds of Dickinsonians who would work and study there.

The College acted as its own contractor, but hired a general manager for the project. Most of the companies that worked on Denny were from the Carlisle area. After the completion of the renovation, Denny Hall was selected as a National Historic Building by the United States Department of the Interior. This was not a bad accomplishment for a building that seemed to have started out as a financial failure.

As noted, the importance of Denny as an academic building was made

clear when an entire disused middle school had to be secured to house classes.

Even today in 1999 Denny remains the primary meeting place for many of

the classes and department offices on campus, especially in the social

sciences. Denny is currently the home of the Departments of

History, Political Science, Anthropology, Sociology, East Asian Studies,

and American Studies.

The Union Philosophical Society Hall after completion, now room 317 |

Denny Hallin 1999, notice the brownstone and the dark

colored Ohio brick on the 2nd floor. |

Photographs courtesy of Dickinson College Web page

The

Denny Clock and Bell Tower, or the Lenore Allison Tower.

Photograph courtesy of Dickinson

College Web page

(Right-click "view image" to

see larger size)

1) Denny Hall Drop File, Dickinson College, Early Cumberland County

2) Denny Hall Drop File, Dickinson College, Early Cumberland County

3) Charles Coleman Sellers, Dickinson College A History (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1973), 287-8, 299

4) James Henry Morgan, Dickinson College 1783-1933 (Harrisburg, PA: Mount Pleasant Press, 1933), 312

5) Denny Hall Drop File, Authentic Pamphlet sent to all alumni and "friends of the College (1895)

6) Charles Coleman Sellers, Dickinson College A History (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1973), 287

7) Denny Hall Drop File, Dickinson College Archives. Authentic Program on the Ground Breaking (1895)

8) Denny Hall Drop File, Dickinson College Archives. Authentic Program of the formal Opening of Denny Hall (1896)

9) Denny Hall Drop File, Dickinson College Archives. Authentic Letter from George Reed

10) James Henry Morgan, Dickinson College 1783-1933 (Harrisburg, PA: Mount Pleasant Press, 1933), 408

11) Charles Coleman Sellers, Dickinson College A History (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1973), 310

12) Dickinson College Trustee Minutes, June 1904, 353-354.

13) Denny Hall Drop File, Dickinson College Archives.

14) Denny Hall Drop File, Dickinson College Archives

15) James Henry Morgan, Dickinson College 1783-1933 (Harrisburg, PA: Mount Pleasant Press, 1933), 364

16) See Denny Hall Rebuilding Account

17) Stacy Bartles, "Denny Hall Restoration Nearly on Schedule," The Dickinsonian, 30 August 1984, p. 4

18) Microcosm, 1984. p. 5

19) Microcosm, 1984. p. 5