© 2000 Dickinson College. All rights reserved

|

Number 13

© 2000 Dickinson College. All rights reserved |

| Education was a matter of great importance in the new American nation.

In this context, Dr. Benjamin Rush–revolutionary, founder of Dickinson

College, and champion of educational reform–was a particularly strong proponent

of learning for young women as well as men. Yet, for all his enlightened

views on the subject, like most of his male contemporaries, he never doubted

the continued subordination of "the female sex."(1)

Nonetheless, when girls and women actually began to attend the kind of

schools Rush advocated, they often came away with a quite different view

of their power and status. In

The Radicalism of the American Revolution,

historian Gordon Wood describes how, in general, members of the revolutionary

elite dreamed of designing an orderly classical republic and were subsequently

alarmed by the democratic forces unleashed by the Revolution. The contrast

between the genteel hopes expressed in Rush's Thoughts upon Female Education,

Accommodated to the Present State of Society, Manners, and Government,

in the United States of America . . .(1787) and the very different

way that women seized educational opportunities in the new republic conforms

to Wood's general paradigm. In education as in other aspects of life in

the new nation, popular democratic transformations profoundly disappointed

the gentlemen who thought they could control the revolution they had unleashed.

Rush's revolutionary disappointment, however, was the nation's achievement.

Rush's plans for women's education were inseparable from his republican ideas about society and politics. As was the case with most of the elite "Founding Fathers," his republicanism traced its roots, not to modern ideas of social equality and majority rule, but to the pre-revolutionary world of the eighteenth-century British Empire. On both sides of the Atlantic, British people had long believed themselves to be the freest in the world. In previous generations, during the English Civil Wars and the Glorious Revolution of 1688-1689, eighteenth-century Britons told themselves, their ancestors had limited the power of their monarchy, beheaded a king, and created a new line of succession to the throne–all for the benefit of the people. On the eve of the American Revolution, however, there were subjects who believed that the Crown was corrupt and abused its power, acting on behalf of a self-interested few, not the good of the subjects as a whole. It was this belief in the corruption of British politics, made evident by the Crown's attempts to strengthen its control abroad, that led many in the colonies to demand change. Their ideas were best expressed in Thomas Paine's Common Sense, which was written, as Paine said, in an attempt to "rescue man from tyranny and false systems and false principles of government, and enable him to be free."(2) Convinced that the corruption of the English monarchy could be eliminated, Revolutionary leaders decided they needed to create their own society, one ruled by a virtuous elite that would act for the good of the nation. To ensure the future survival of such an elite, the revolutionaries pinned their hopes on a system of education designed to shape young men and women into virtuous citizens. |

Benjamin Rush.

|

Before the Revolution, and before their conversion to republican values, most colonists thought rudimentary learning was more than adequate for the limited needs of girls. Parents taught reading and writing to children of both sexes at home. To supplement their education, girls could enroll in dame schools, institutions usually established by women who needed a means of financial support. Girls received advanced training only if their parents were willing and able to pay for more education and if an "adventure school" was available. Adventure schools were often extremely short-lived and were located in the homes of the instructors, usually women, or married couples, but by the 1760s, nearly every colonial city had one. The course of study at these establishments stressed ornamental education in such areas as music, dancing, and needlework. This reflected the traditional notion that women's ultimate goal should only be marriage and that the purpose of education should be to make them more attractive to possible suitors. Many colonists accordingly saw scholarly learning for women as selfish because it detracted from domestic and familial duties. The question of higher education was largely irrelevant, however, because most women were not even capable of basic reading and writing. Illiteracy, historian Linda Kerber concludes, "could not be excused in a man," but, "was pardonable in a woman, because less was expected from her."(3) |

| As a result of their education, or lack thereof, pre-revolutionary

women engaged in little communication outside of their families, households,

and local communities. Women seldom handled land or commercial transactions

or involved themselves with local politics. Yet, the ordeals of women during

the Revolution, when the wartime absence of their husbands forced them

to take responsibility for the survival of their families and households,

irrevocably altered their lives and those of future generations.(4)

Wartime experience convinced many Americans that women needed broader training

to prepare them for unexpected contingencies.(5)

The creation of a republican form of national government provided a further impetus for changes in the educational opportunities for women.(6) The republican ideology of the Revolution led the now-independent citizens to insist on virtue in their government. Because, as Kerber explains, "republics rested on the virtue of their citizens, Revolutionary leaders had to believe not only that Americans of their own generation displayed that virtue, but that Americans of subsequent generations would continue to display the moral character that a republic required."(7) As what a clergyman of the day called the "first and most important guardians and instructors of the rising generation," women were the ones who would nurture virtue in their sons, the leaders of the future, and would need to be properly educated for that important task. To this effect, failings in women's education were perhaps even more dangerous than in men's because of their "most powerful influence on society, as wives, as mistresses of families, and as mothers."(8) Such republican beliefs inspired the development of educational plans all over the country to serve the national interest by educating both boys and girls. A 1795 American Philosophical Society essay contest revealed the popularity of these ideas. On the subject of an American system of education, every entry proposed universal schools, free and open to both sexes.(9) There were, of course, opponents to educating women. When the American Philosophical Society ran a second essay contest in 1797, most entries excluded women from education. In fact, Samuel Harrison's winning essay proposed that "every male child, without exception, be educated," obviously omitting girls from his plan. Samuel Knox, the other prize recipient in the same year, proposed opening primary schools to girls, but not colleges or academies.(10) Views such as these tended to be supported by the thought that women were not citizens in the same manner as were men. Citizenship, to some, meant the ability to control property independently and to bear arms in defense of the republic, roles from which women were almost universally excluded.(11) Education for women was also denounced out of the fear that learned women would find interests and careers outside of their domestic concerns. Female literacy and education would enable women to establish communication networks wider than their localities, thereby gaining access to other points of view, and possibly promoting skepticism about local opinions and practices. Scholarly learning for women would then throw the social system into chaos by challenging a woman's "traditional life pattern of unremitting physical toil and unremitting social subservience." Educating women also meant narrowing the supposed disparity between the reason and intellectual strengths of the sexes. Men might no longer be seen as the intellectual superiors of society if women were granted the same educational opportunities as males.(12) Yet arguments against educating women were in the minority, while proponents of female education, like Dr. Benjamin Rush, led the way in educational reforms for the good of the republic. Rush was an ardent supporter of educational reform, especially for women. Believing that education should promote the success of the new republic, he contended that children should "be instructed in all the means of promoting national prosperity and independence, whether they relate to improvements in agriculture, manufactures, or inland navigation."(13) Rush wanted to create a system of education in Pennsylvania, and eventually the entire nation, with free schools in every town that had one hundred or more families. Reading, writing, and arithmetic would be taught to all, so that everyone would become "one great and enlightened family." These schools would ingrain students with republicanism, creating a national character and uniting the country.(14) |

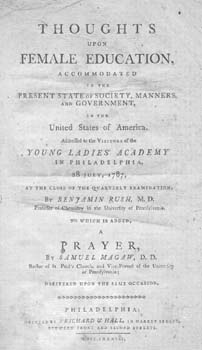

| Rush's Thoughts upon Female Education, which he gave as a speech to visitors of the Young Ladies' Academy in Philadelphia in 1787 and published later in same year, showed him to be a firm believer in "republican motherhood," the idea that women's main duty was to raise sons to be virtuous citizens. Female education, he believed, was of the utmost importance, because "the first impressions upon the minds of children are generally derived from women."(15) He also recognized that because women were the caretakers of children, women "must concur in all our plans of education for young men, or no laws will ever render them effectual."(16) To qualify women for this purpose, Rush wanted them to be instructed in the usual branches of female education, such as sewing and housekeeping, as well as in the principles of liberty and government. Patriotism should be deeply ingrained in women's thoughts. Furthermore, Rush recognized that women had a stabilizing influence over men, who "would then be restrained from vice by the terror of being banished from their company." As nurturers of virtue in society, women deserved to be properly educated.(17) |

Title page of Rush's Thoughts upon Female Education (1787). Department of Special Collections, Dickinson College Library. |

| Rush also believed that women's education would save American society

from the decay that had ruined British society and made the American republican

revolution necessary. Because it was time to change the attitude and behavior

of Americans to suit the unique form of the new government, women's education

needed to be based not on the ornamental instruction prevalent in British

society, but on the principles of liberty, justice, and knowledge so necessary

in a republic. In Rush's opinion, the United States placed too much value

on British cultural models. Ladies' fashion, for instance, was designed

for the much cooler British summer climate, and was incongruous to conditions

in America, just as the criminal laws taken from Great Britain, whose society

was so old and corrupt that executions were a source of national entertainment,

were incompatible with the new republican order. Although Rush thought

that society in the United States, as in Britain, was likely to decay over

time, he was convinced that the decay could be prolonged, if not prevented,

by educating women appropriately. By doing so, Americans could hope that

their government would not become corrupt and abusive of power, as the

British monarchy supposedly had done.(18)

Rush espoused the idea that education in America should be different from that in England because of the differing roles of married women in the two countries. Women in America married much earlier than they did in Great Britain. Early marriage, "by contracting the time allowed for education, renders it necessary to contract its plan and to confine it chiefly to the more useful branches of literature," not the superfluous subjects studied in Great Britain, such as foreign languages. The nature of property-holding in the United States, where citizens often had several different occupations at once to improve their fortunes, also differed from Great Britain. Thus, women in the United States also had to be prepared to be the "guardians of their husbands' property." The best education would be one that taught women how to "discharge the duties of those offices with the most success and reputation." Of the utmost importance, Rush believed, was that women knew how to read, speak, and spell the English language correctly. It was also necessary, in Rush's view, that women be able to write legibly and properly. Moreover, as a steward of her husband's property, a young lady should be knowledgeable in bookkeeping. Such skills would prepare women to better assist their husbands.(19) Rush further asserted that education for American women needed to be different than in England because of the nature of the American government and economy. Republican principles, unlike the monarchical doctrines of Great Britain, ensured the "equal share that every citizen has in the liberty, and the possible share he may have in the government of our country." It therefore became necessary that women "should be qualified to a certain degree by a peculiar and suitable education, to concur in instructing their sons in the principles of liberty and government." The state of the American economy also created a need for the practical education of women. The Napoleonic wars in Europe caused an increased demand for American goods, and international trade exploded. Men were too busy trying to earn their fortunes to deal with such domestic concerns as child-rearing. Women were left to raise and teach their children, and needed to be suitably educated to do so. Finally, compared to Great Britain, America was lacking in servants. The abundance of land and opportunities to gain riches made servitude unappealing to colonists and recent immigrants, unlike in Great Britain, where chances for advancement in society were almost nonexistent. Servants in the United States, when available, were less educated and less subordinate, Rush thought, and so women were necessarily obliged to handle more of the private affairs of their families than ladies of the same social status in Great Britain.(20) In keeping with such practical considerations, Rush believed that education should dispel silly behaviors and ideas from women. He particularly stressed the reading of history, instead of fiction, especially novels. To be able to read history better, a woman should master geography and chronology, which would "thereby qualify her not only for a general intercourse with the world, but, to be an agreeable companion for a sensible man."(21) A little astronomy and philosophy should also be learned "particularly with such parts of them as are calculated to prevent superstition, by explaining the causes or obviating the effects of natural evil."(22) Nevertheless, Rush realized the value of some ornamental education. Training in vocal music was part of his basic plan because it prepared a young woman for singing in church and had an ability to "soothe the cares of domestic life." According to Rush, "the distress and vexation of a husband–the noise of a nursery, and, even the sorrows that will sometime intrude in to her own bosom, may all be relieved by a song." Singing also helped to prevent sickness by strengthening the lungs. Dancing–or rather what we would today call rhythmic exercise–was also to be encouraged because it promotes health and "renders the figure and motions of the body easy and agreeable."(23) Instruction in religion was probably the most important part of Rush's plan for educating women. Bothered by the prejudice, zeal, and bigotry of society, Rush wrote that religion was "necessary to correct the effects of learning" and that instruction in Christianity and the principles of the different sects prevented bigotry by "removing young men from those opportunities of controversy which a variety of sects mixed together are apt to create and which are the certain fuel of bigotry."(24) In Rush's eyes, "the fear of the Lord" was "the beginning of all wisdom and should be the end and object of all education."(25) Rush was certain that Christian philosophers made the most scientific discoveries and that the most Christian nations were also the most learned. Christianity, therefore, was the most effectual way to promote republican knowledge and virtue in the United States.(26) |

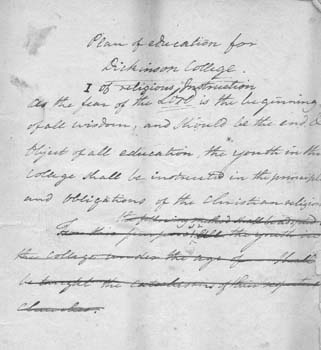

Rush's draft of a "Plan of Education for Dickinson College" (1785), although never fully implemented, shows the importance he attached to the role of religion in education. Section I reads, "As the fear

of the Lord is the beginning of all wisdom, and should be the end &

Object of all education, the youth in this College shall be instructed

in the principles and obligations of the Christian religion."

|

If Rush was specific in his views of what women

should be taught, he was equally specific about what they should not be

taught. Learning to play musical instruments was a waste of money and time.

Instruments cost too much, instructors over-charged, and practice distracted

women from mastering things more important and practical. Eventually, Rush

complained, wives' "harpsichords serve only as side-boards for their parlours,

and prove by their silence that necessity and circumstances, will always

prevail over fashion, and false maxims of education." Rush objected to

instruction in drawing for the same reason–too much time was needed to

become proficient in the art. Learning foreign languages, such as French,

was equally wasteful because women were rarely in contact with foreigners.

Moreover, the truly valuable French books were already translated into

English.(27)

Rush also disapproved of learning classical languages because the use of

the vernacular was more consistent with republican principles.(28)

The emphasis on classical learning served to widen the gap between not

only men and women, but rich and poor, as well. Furthermore, some of the

Latin and Greek classics were "unfavorable to morals and religion," and

so should be avoided by both men and women. "Indelicate amours and shocking

vices both of gods and men fill many parts of them," he argued. "Hence

an early and dangerous acquaintance with vice; and hence, from an association

of ideas, a diminished respect for the unity and perfections of the true

God."(29)

Although Rush was a proponent of women's education, his views often fell short of egalitarianism. Rush proclaimed that if his measures were instituted and women had a sense of their religious and moral obligations to society and their country, "the government of them will be easy and agreeable" because " weak and ignorant women will always be governed with the greatest difficulty."(30) Certainly, in Rush's opinion, education would serve to make women more malleable and submissive to men. Properly educated women would appreciate their natural inferiority and conclude that men were, by design and by right, the natural leaders of the world. Rush once wrote to Rebecca Smith, a friend who asked for advice on her upcoming marriage, "Don't be offended when I add that from the day you marry you must have no will of your own. The subordination of your sex to ours is enforced by nature, by reason, and revelation. Of course it must produce the most happiness to both parties."(31) Rush–like many elite American revolutionaries–saw no contradiction between this side of his views and the egalitarian rhetoric of his republicanism. |

| In spite of what by today's standards seems an attempt to educate women

to accept their own oppression, the improvement of schooling was still

the most important social change for women in the early republic. Educational

reforms, Kerber concludes, "opened the way into the modern world" for women.(32)

From the 1780s to the 1800s, there was a boom in the establishment of female

academies, making higher education available to more middle and upper class

girls. This was especially true in the case of New England, although less

so in the South, which was still far behind in education because its wartime

losses were greater than in the North and occurred in the later years of

the Revolution.(33)

The new academies open to women differed greatly from the adventure schools before the Revolution. Offering only minimal ornamental instruction, the academies stressed composition, history, and geography. The use of grammar books and weekly journals forced girls to perfect their writing. Little to no instruction of classical languages was given because, perhaps due to Rush's influence, such languages were becoming seen only as decorative even for men to learn.(34) The academies were also built in small towns and accepted boarders from all over the nation, whereas adventure schools mainly existed in larger, more populated cities. Young women who attended them attained a new sense of personal independence apart from their families, while forming lasting bonds with friends from diverse backgrounds. Also, unlike adventure schools, the new schools were able to develop an institutional base, acquiring permanent buildings, hiring more staff relative to the number of students, and relying on financial support from their communities. With this more permanent standing, the academies were able to develop their curricula more fully and offer more to students than previously experienced in the country.(35) The effects of the educational reforms in the early republic included a change in thinking about women's education. As historian Mary Beth Norton has shown, whereas female education had previously been viewed as a novelty, after the American Revolution, parents began to think of educating their daughters as a duty. Young women themselves, rather than tolerating education merely to improve their chances at a good marriage, began to value the opportunities available to them. Realizing that they were more fortunate than members of any previous generation, young women were determined to take full advantage of their educational opportunities and often coerced their parents into letting them continue schooling. Anxieties on the part of parents and students about being separated for the cause of learning only illuminated the importance placed on women's education. Boarding was a novel experience, perhaps harder on parents and students because of its novelty, yet it was tolerated because learning was believed to be so worthwhile. Education earned women a much higher place in society than ever before.(36) Contrary to the hopes of Benjamin Rush, educational reforms in the early republic also served to empower women. Women were no longer divided into their separate households, but were opened up to the outside world. More women petitioned for divorce in the late 1700s, chose to remain single, and developed interests outside of the home as well as friendships with other women. Shared educational experiences, one scholar observes, "must have given some women the courage to reevaluate their lives."(37) Benjamin Rush believed that "by the separation of the sexes in the unformed state of their manners, female delicacy is cherished and preserved."(38) What he had not counted on, however, was that, in groups, women would come to realize their own power. As historian Nancy Cott concludes, the "orientation toward gender in their education fostered women's consciousness of themselves as a group united in purposes, duties, and interests. From the sense among women that they shared a collective destiny it was but another step (though a steep one) to sense that they might shape that destiny with their own minds and hands." Indeed, as many men had previously feared, women, "aware of wider perspectives . . . put their minds to work at other purposes than refining their subordination to men." The feminists of the mid-nineteenth century were predominately well-educated. Far from leading them to accept the argument that women were naturally inferior to men, their educational experience revealed to them the opposite–that women, given the opportunity, were intellectual equals of men, and, as such, were worthy of controlling their own lives.(39) If Benjamin Rush had seen the effects of the reforms that he advocated in women's education, he would have been greatly disappointed. Like other elite revolutionaries of his time, Rush was no egalitarian. The purpose of educating women, in his mind, was to make them more submissive and easily controllable, not to enlighten them about their intellectual capabilities. Instead, education had the opposite effect of liberating, not subduing, women, just as the American Revolution more generally, as Gordon Wood has shown, created a rambunctiously democratic nation in the place of the orderly classical republic of which the elite dreamed. Rush, like so many of the Founding Fathers, became disillusioned with not only the effects of the American Revolution, but with the effects of educational improvements as well. He had hoped that his system of education would render "the mass of the people more homogenous, and thereby fit them more easily for uniform and peaceable government."(40) Instead, towards the end of his life, he saw education allowing people to think for themselves, and the ideas they developed did not match his dreams for the future of the United States. Perhaps that is why he wrote in 1810, " Let a learned education become a luxury in our country for should learning become universal it would be as destructive to civilization as universal barbarism."(41) |

|

Number 13

© 2000 Dickinson College. All rights reserved |