Charles Francis Himes at work

Courtesy of the Dickinson College

Archives

by Regan Winn '02

Charles Francis Himes at work

Courtesy of the Dickinson College

Archives

The founding of Dickinson College came at a time of not only political intensity, but scientific as well. Innovations such as the discovery of Oxygen by Joseph Priestley in 1774 and the emergence of Lavoisierís1 broad interpretation of the phlogiston hypothesis2, which later became the foundation of Modern Chemistry, were only the beginnings of this scientific awakening.3 This was a time of constant discussion and debate surrounding new and old chemical facts and theories. The College could not afford to overlook this surge in science while establishing its original course plan. Since its founding in 1783, natural science has played a critical role in Dickinsonís curriculum. The department flourished as a result of many brilliant and dedicated men whose revolutionary ideas of science made Dickinson a pioneer in this field.4

It was Dr. Benjamin Rushís enthusiastic interest in the area of science which laid the foundation for an ever-evolving, highly progressive program.5 Not only was he a teacher and politician, but he was a physician as well, which gave him first-hand knowledge of the importance of concentrating on all areas of study including science.6 Dr. Rush held the prestigious honor of being named the first Chair of Chemistry in America while he was with the medical department at the University of Pennsylvania in 1769. He took this interest and knowledge of the sciences and applied it to the curriculum at Dickinson. His well-rounded education allowed him to see the need for equally strong humanities and science programs and caused him to encourage the institution of both. In 1784, Rush served as a member of the committee to engage someone to teach science. It was decided that scientific instruction would be provided mainly by lectures. At this time, chemistry was taking the prominent position as the science to learn and, therefore, was the primary area of focus for the curriculum.7

The seal of the College has a telescope incorporated into it at the persistence of Rush and it was he who ensured that money be allocated for philosophical apparatus from time to time.8 He incorporated the need for apparatus in the plans for soliciting funs for the College along with requesting that the Honorable Mr. Bingham secure aid abroad.9 In 1784 he purchased the core of the collection: an electrical-machine, barometer, thermometer, and others which were not enumerated in detail. For years he continued his quest for additional apparatus collecting pieces from all over the world.10

The Seal of the College

Courtesy of the Dickinson College

Archives

Dr. Charles Nisbet, the first President of Dickinson College, helped to reinforce Rushís push for a strong science curriculum. Nisbet, himself, was personally acquainted with the physical sciences. His influences at the University of Edinburgh, where science was always more recognized and encouraged than in the University of England, gave him an intellectual appreciation for a curriculum divided between the humanities and the sciences.11 In a conversation on one of his visits with Governor Dickinson at Wilmington, Nisbet commented on the probable effect of a zealous prosecution of study in the physical sciences which indicates some degree of familiarity on the subject:

"...unless the grace of God produced a different effect, the more intimately men became acquainted with the works of nature, the less mindful were they of their great author"12

Nisbet was fully capable of appreciating the earnest efforts of Dr. Rush to increase the efficiency of instruction in the sciences and to provide assistance as well.13

Although he is predominantly recognized in connection with the principalship at Dickinson, Dr. Robert Davidson, the third member of the faculty, also made quite an impact on the science department. He was appointed the principal pro-tempore for five years following Dr. Nisbetís death, but prior to that he was a professor.14 After the Board found Professor Robert Johnston to be inadequate, Davidson took on the position as Professor of Natural Philosophy from 1787-1792. He was no stranger to all areas of science. He published some papers on astronomy and constructed an ingenious piece of apparatus, the cosmosphere, which supposedly solved many celestial problems, but was lost after his death. His son, Reverend Robert Davidson, D.D. was given the wrong piece and never recovered the original. Under special direction of the Board, he also gave instruction in Geography and the use of globes. Dr. Davidson left many of his carefully prepared lectures on scientific studies and an epitome of geography in verse which was published during his connection with the University of Pennsylvania in the care of the College.15

After the election of Reverend Jeremiah Atwater as the permanent principal in 1809, a resolution was made to establish a Chair of Natural Philosophy and Chemistry.16 Dr. Thomas Cooper was suggested to fill the position, but this proposal was met with reluctance by some members of the Board of Trustees. Dr. Cooper served as a judge for eight years until he was impeached and removed in times of high political excitement. This fact coupled with his tendency to be acquainted with known radicals of the day led to some opposition to his election.17 The Board expressed their concern that the:

"...election of Mr. Cooper would prove highly injurious to the interest and reputation of the College, in consequence of the prejudices entertained by the public against him".18

Nevertheless, he was elected to the Chair and, at considerable inconvenience to him, entered the position a few months earlier than he had intended. Two days after taking the Oath of Office on August 7, 1811, his Introductory Lecture on Chemistry was delivered in the "public hall" of the College and was attended by the entire Board of Trustees as well as the students. This lecture was published by order of the Board and was among the earliest published scientific lectures in this country. The lecture, alone, filled 100 pages and Cooperís accompanying notes added 136 additional pages covering a broad range of scientific information. This famed lecture began with a general observation on manís relations to his environment and a general classification of scientific knowledge including reasons for anticipating a course of lectures on Chemistry by a history of that science.19 Cooper claimed to know of no tolerable history of Chemistry in the English language, but, instead, turned to the Scriptures for chemical facts because they carry the "...marks of internal evidence that entitle them to great consideration".20 In addition to his well known lectures, Dr. Cooper also revived one of the earliest journals of general science published in America, Emporium of Arts and Sciences, which he continued to publish throughout his career.21

When the Methodist Episcopal Church assumed control of the College, Reverend John P. Durbin, D.D. became the organizing head of the College on June 7, 1833. He is recognized as leading the rebirth and reorganization of the College.22 In the December 1834 Catalogue of the Officers and Students of Dickinson College, in an addendum at the end of the description of student expectations, Dr. Durbin writes:

"As it is conceived, however, that after all, the grand design of education is to excite, rather than to pretend to satisfy, an ardent thirst for information; and to enlarge the capacity of the mind, rather than to store it with knowledge, however useful; the whole system of instruction is made subservient to this leading object".23

Durbin was a strong advocate of a form of teaching which encompassed the full scope of human learning.24 He vowed to make instruction in the sciences as proficient as in any other college.25 As a Professor of Natural Science at Wesleyan University prior to coming to Dickinson, Dr. Durbin was already familiar with science and its importance for a full liberal arts education. During the reorganization of the faculty in 1834, he was quick to fill the professorship of Natural Science as well as making extensive efforts to increase the collection of scientific apparatus.26 In doing so, he managed to acquire a collection of apparatus from Professor Walter R. Johnson of Philadelphia, the secretary of the Franklin Institute.27 The transport of this collection was superintended by William H. Allen, who shortly after, filled the position of Chair of Natural Science.28 During his time as Chair, according to his students, he had a solid reputation for being a strong and clear lecturer and a harsh advocate of memorization and recitation.29 However, in 1848, he was made Chair of English Literature and Philosophy and Spencer Fullerton Baird was elected to take Allenís position. Baird had been connected with the College since 1845 as Curator of the Museum.30 He had an intense interest in science, particularly in natural history, which he brought to Dickinson.31 While he was the Chair of Natural Science, he continued his devotion to Natural History, particularly Ornithology, publishing a descriptive list of the surrounding flora in the area. He often made excursions through Pennsylvania in pursuit of facts and specimens connected with his beloved studies as a hands-on learning tool. He resigned in 1850 to continue his work as Assistant Secretary at the Smithsonian Institute where he took charge of the National Museum.32 Reverend Erastus Wentworth, D.D. was unanimously chosen as his successor. Immediately after graduating from Cazenovia Seminary and Wesleyan University, Wentworth taught Natural Science in academies in New York and Vermont. The department was not enlarged or made particularly prominent under him, but he was still known as a popular lecturer.33 Reverend Wentworth only spent a short time teaching at Dickinson before he traveled to Foo Chow, China to pursue missionary work in 1854.34

Burning-Lens and Air-Gun of Dr.

Priestley.

Rotascope of Professor Walter R. Johnson.

Courtesy of the Dickinson College

Archives

Around 1855, William C. Wilson replaced Reverend Wentworth as lecturer of Natural Science. Under his direction, efforts began to be made to expand the courses of scientific study, but with no permanent effect. An Astronomical Observatory was constructed in 1857 through the Department of Astronomy fully equipped with an Achromatic telescope which was the most technologically advanced instrument of its time. Due to the concentrated efforts of Professor Wilson, a science course in Geology was added in the sophomore year in 1859. However, under the new president, Reverend Herman M. Johnson D.D., the option was removed and the original junior and senior year curriculum was reinstated. Professor Wilson was not satisfied with the limited range of facilities offered by the College, so during vacations, he took advantage of the opportunity to study in a laboratory with the eminent chemist, Dr. F.A. Genth of Philadelphia who later became a professor at the University of Pennsylvania. He also made contributions to the Quarterly Review on various scientific matters. Ten years after his career at Dickinson began, Wilson died on March 2, 1865 due to a disease he contracted from the ill-ventilated labs where he spent so much of his time.35

About the close of the first quarter of the century, influences of science in America sparked debate and discussion of the various branches of science in relation to the College. The question of how a liberally educated man could afford to be ignorant of the facts and laws of the material universe was raised. Baby steps were taken in the advancement of he status of the science curriculum at Dickinson. First, it was imperative to recognize the need and value of classical languages and physical science as a beneficial background for a liberal education. As a starting point, a system of parallel elective courses was developed. At certain stages in a studentís college career, a selection of studies to suit their "curiosities" was permitted. At this time, the curriculum tried to encompass all aspects of science within the junior and senior years. As the program developed further, the courses began to narrow their areas of study and the professors began to specialize in certain branches of science making it a more regimented curriculum.36

Charles Francis Himes 1900

Photograph Courtesy of Dickinson

College Archives

At the time of his death, Wilson requested that a prominent former student of his, Charles Francis Himes, replace him as Professor of Natural Science. Himes accepted the position under the condition that elective laboratory work in the senior year be recognized as part of the regular courses taken toward a Bachelor of Arts degree.37 The Board of Trustees met in June 1865 and a committee proposed the establishment of enlarged elective course offerings in the area of Natural Science. They decided that these courses could be substituted for Greek in the junior year and for Latin or Greek with one afternoon of laboratory work in the senior year as purely elective courses, however.38

At once, Himes began to organize an elective laboratory course in Chemistry which, according to a report from the National Commissioner of Education, was one of the very first in the country.39 A new Natural Science curriculum was instituted consisting of three recitations and two lectures per week for junior and senior classes throughout the year. Dickinson College was among the earliest institutions of higher learning to inaugurate such a course into their curriculum. It advocated vast, expansive knowledge of all branches of science, not simply one specific focus. Three methods for teaching Natural Science were established with the intent that all three should complement each other. Teaching by textbooks and recitations, by lectures accompanied with experimental illustrations, and by experiments and investigations performed by the students were all incorporated into the curriculum. The first course to utilize this expanded curriculum was one in chemical analysis.40

Upon the arrival of Professor Himes, a plethora of changes unfolded. First came the formation of the Scientific Course designed for young men who did not want to study the classics. The complete course included English Literature, Modern Language, practical Chemistry, and pure and applied mathematics. Students were given instruction in qualitative analysis, practical Chemistry, analytical tables, mineralogy, biology, and botany. In conjunction with this new plan, Professor Himes also reorganized the science courses to make a more disciplined curriculum extending it to include three years of study. Now students were offered chemistry in their sophomore year, physics with a lab course their junior year, and geology and mineralogy with a lab course their senior year. Qualitative analysis in the latter two years of study in place of Greek and Latin remained the same.41

The next major hurdle was the inadequacy of the building space and equipment. To remedy the laboratory space problem, one was made on the ground floor of South College which accommodated approximately twelve students, but lacked most modern appliances. By the annual Board of Trustees meeting in 1866, the College decided to formally adopt a plan with a more suitable room on the main floor of South College to act as a laboratory. The College provided the necessary funds along with an additional twenty-five dollars per year paid by each student taking the course, but this would only solve the problem for the time being.42

The following year, Professor Himesí second year at Dickinson, the College curriculum was broken into three areas of concentration: Biblical, Scientific, and Law. The Board of Trustees created ten departments of study including physics and mixed mathematics, chemistry, physical geology, natural history, mineralogy and geology, and civil and mining engineering. There was also an option added for those students who were interested in going on to medical school. They could take certain science and math courses that were designed specifically as preparatory work for their desired field.43

Click on image to view Himes' laboratory rules

Courtesy of the Dickinson College

Archives

That same year, with Professor Himes as the director, students enrolled in the science program formally organized the Scientific Society of Dickinson College with the goal of extending their knowledge of the numerous branches of Natural Science in which they were studying and to provide a facility for their studies. Its purpose was strictly for the improvement and instruction of its members. This society served as a truly beneficial addition to the ordinary methods of instruction. They generally met in the lecture room of South College where they would present abstracts of items of general scientific interest through lectures, experiments, and reports selected from a variety of scientific periodicals on relevant material being covered in class. The Scientific Society Prize was created and presented to a member of the Senior class who gave the fullest and most scientific account of experiments made upon some subject selected by the Society.44 Its seal, a ray of light from a star decomposed by a prism, was chosen with the intent of noting the "...cosmical character, then, but recently imparted to chemistry by the spectroscope...."45 From the founding to 1876, there were a total of 126 members and 4 honorary members: Professors Spencer F. Baird, Ogden Rood, Henry Morton, and Theodore Wormley.46

Himes introduced his photographic methods to the Society by opening the photographic laboratory to the members for observation and research. The Scientific Society published ceratin photographs which they sold to the community. Such photos included portraits of distinguished graduates since 1783, educational subjects such as apparatus and objects grouped for illustration of particular subjects in Natural Science, lecture-diagrams and cuts from scientific publications, historic pieces of apparatus in the collection of the College, and portraits of celebrated men of science.47

Numerous advances were made in the Natural Science department under Himesí direction throughout his career at Dickinson. Each student was guaranteed a desk, apparatus, chemicals and the use of text-books for twenty-five dollars a year. General books of reference and leading scientific journals were readily accessible as well as texts and references in German for those students who were proficient in the language. Practice exercises were arranged for qualitative analysis, such as the use of a blow pipe and the determination of certain commoner minerals. There were also quantitative analysis exercises available on topics such as urinary analysis, toxicology, and photographic chemistry. An experimental course in physics was instituted with experiments in light, electricity, sound, heat, lantern projections, and the use of a spectroscope, photometer or a camera. A Teacherís Course was arranged for those students who also wanted to give instruction in natural science. This course embraced instruction in the use and care of apparatus employed for illustration in natural philosophy and chemistry and apparatus for instruction in those branches. At the interest of Himes, a photography course was also added to the curriculum. It included instruction in the collodion process, silver and carbon printing, the emulsion process, the preparation of photographic chemicals and the methods for recovery of photographic waste.48 Beginning in 1871, there was an influx of donations of scientific apparatus which carried on for a number of years contributing to the constant expansion of the scientific library.49 In 1877, a new degree, Bachelor of Philosophy, was instituted for those who chose to take the Scientific Course route in place of the classics which was renamed the Latin-Scientific Course plan.50

Professor Himesí final decade as a member of the Natural Science department saw many more modifications and advancements. The curriculum reverted back to offering science only in the junior and senior years allowing students to focus intensely on science in those two years if they so desired. The Board of Trustees created yet another new course plan, the English-Scientific Course with a focus on science and English, but not Greek or Latin. This plan had the same basic premise of the Latin-Scientific plan, but replaced any classical study with English. The scientific focus and course study remained the same, however.51

Gradually, the department began to specialize and add more professors to their faculty roster. In 1885, Professor Himesí title became simply Professor of Physics and Chemistry and Fletcher Durell was named Professor of Astronomy.52 The very next year, Professor Himesí title narrowed further to only involve physics and William B. Lindsay was named adjunct Professor of Chemistry. This allowed the professors to focus on a more regimented classification of science and moved away from the broad-based curriculum of the past.53

Himes' Great Vision - The Tome Scientific Building

Sketch of Tome Scientific Building

Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper

June 20, 1885

Courtesy of the Dickinson College

Archives

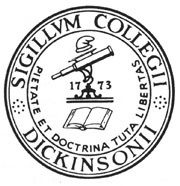

In all of his years of teaching at Dickinson College, the one persistent obstacle seemed to be the search for ample space for the Natural Science department. South College soon became inadequate to accommodate the expanding department once again. In 1878, Professor Himes reported that the Natural Science department had reached its limit of growth and efficiency with its present location. Therefore, he proposed that a building with proper space be completed by the centennial of the College in 1883.54 He worked with Spencer F. Baird of the Smithsonian Institute and Montgomery Cunningham Meigs, a Smithsonian architect, to develop a basic layout for the building.55 It was to have two lecture rooms, two laboratories for chemistry and physics, two offices and private laboratories for the professors, and the necessary rooms to store apparatus. It was also to house the ever-growing scientific library and College museum. The Board of Trustees looked favorably upon this and passed a resolution authorizing him to raise $25,000 for the erection of the building.56 According to Himes, it was to "...be a building not for the sake of a building, but for the sake of its uses, and to meet the wants of the College...."57 The Trustees conducted a financial drive to mark the centennial of the College charter which took donations for the repairs and modernization of the buildings on campus as well as for the construction of the new science building. Jacob Tome, a Trustee of the College, generously donated the full $25,000 to fund the building which now honorably holds his name.58

Original plans for Tome Scientific Building sketched

by Himes

Courtesy of the Dickinson College

Archives

At the opening of the Tome Scientific Building, on June 24, 1885, Himes delivered the inauguration address. He saw the construction of this building as a huge step in science education at Dickinson. It was a transition from the old to the new. He is quoted as saying, "Behind us more than a century of achievement, before us unlimited possibilities of the future".59 The purpose of Tome was to make the College as competitive and competent as any other institution of higher education. His goal was to "...bring scientific instruction in this institution up to a high ordeal...."60 It was to serve as a progressive tool for hands-on scientific learning which it has successfully accomplished for many years.61

As a final note, the science department at

Dickinson College is still to this day expanding and improving. Without

the initial display of such intense interest by so many outstanding intellectuals

in the Collegeís history, the department would not be the same. Charles

Francis Himes brought Dickinson into the rapidly growing world of science

and placed it among the most prominent institutions of higher learning

in his time. Many significant and crucial advancements were made under

the direction of Himes and for that, the College and all of its students,

past, present, and future, should be most grateful.

Endnotes

1. Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier was a French scientist, usually regarded as the "Father of Modern Chemistry". He was a brilliant experimenter and many-sided genius who was active in public affairs as well as in science. (Britannica Online: Lavoisier, Antoine-Laurent).

2. Phlogiston is a hypothetical substance, representing flammability, postulated in the late 17th century by the German chemists Johann Becher and Georg Stahl to explain the phenomenon of combustion. According to the phlogiston theory, every substance capable of undergoing combustion contains phlogiston, and the process of combustion is essentially the process of losing phlogiston. (Yahoo: phlogiston process: http://www.fukc.com/encyclopedia/low/articles/p/p019001256f.html).

3. Charles Francis Himes, A Sketch of Dickinson College. (Harrisburg, PA: Lanes Hart, 1879)

4. Charles Francis Himes, A Sketch of Dickinson College. (Harrisburg, PA: Lanes Hart, 1879)

5. Scientific Society History and Roll. Found in the Charles Francis Himes Family Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, PA.

6. James Henry Morgan, Dickinson College 1783-1933. (Harrisburg, PA: Mount Pleasant Press, 1933)

7. Charles Francis Himes, A Sketch of Dickinson College. (Harrisburg, PA: Lanes Hart, 1879)

8. Scientific Society History and Roll. Found in the Charles Francis Himes Family Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, PA.

9. Charles Francis Himes, A Sketch of Dickinson College. (Harrisburg, PA: Lanes Hart, 1879)

10. Charles Francis Himes, A Sketch of Dickinson College. (Harrisburg, PA: Lanes Hart, 1879)

11. Charles Francis Himes, A Sketch of Dickinson College. (Harrisburg, PA: Lanes Hart, 1879)

12. Charles Francis Himes, A Sketch of Dickinson College. (Harrisburg, PA: Lanes Hart, 1879)

13. Charles Francis Himes, A Sketch of Dickinson College. (Harrisburg, PA: Lanes Hart, 1879)

14. Charles Francis Himes, A Sketch of Dickinson College. (Harrisburg, PA: Lanes Hart, 1879)49-50.

15. Charles Francis Himes, A Sketch of Dickinson College. (Harrisburg, PA: Lanes Hart, 1879)94-95.

16. Charles Francis Himes, A Sketch of Dickinson College. (Harrisburg, PA: Lanes Hart, 1879)50-51.

17. Charles Francis Himes, A Sketch of Dickinson College. (Harrisburg, PA: Lanes Hart, 1879)97.

18. Charles Francis Himes, A Sketch of Dickinson College. (Harrisburg, PA: Lanes Hart, 1879)98.

19. Charles Francis Himes, A Sketch of Dickinson College. (Harrisburg, PA: Lanes Hart, 1879)98-99.

20. Charles Francis Himes, A Sketch of Dickinson College. (Harrisburg, PA: Lanes Hart, 1879)99.

21. Charles Francis Himes, A Sketch of Dickinson College. (Harrisburg, PA: Lanes Hart, 1879)99-100.

22. James Henry Morgan, Dickinson College 1783-1933. (Harrisburg, PA: Mount Pleasant Press, 1933)248.

23. Dickinson College Catalogue 1823-1845. Catalogue of the Officers and Students of Dickinson College, Dec 1834 edition. 12.

24. James Henry Morgan, Dickinson College 1783-1933. (Harrisburg, PA: Mount Pleasant Press, 1933)248.

25. Scientific Society History and Roll. Found in the Charles Francis Himes Family Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, PA.

26. Charles Francis Himes, A Sketch of Dickinson College. (Harrisburg, PA: Lanes Hart, 1879)104.

27. Scientific Society History and Roll. Found in the Charles Francis Himes Family Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, PA.

28. Charles Francis Himes, A Sketch of Dickinson College. (Harrisburg, PA: Lanes Hart, 1879)105.

29. Charles Francis Himes, A Sketch of Dickinson College. (Harrisburg, PA: Lanes Hart, 1879)105-106.

30. Charles Francis Himes, A Sketch of Dickinson College. (Harrisburg, PA: Lanes Hart, 1879)106-107.

31. Scientific Society History and Roll. Found in the Charles Francis Himes Family Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, PA.

32. Charles Francis Himes, A Sketch of Dickinson College. (Harrisburg, PA: Lanes Hart, 1879)107-108.

33. Charles Francis Himes, A Sketch of Dickinson College. (Harrisburg, PA: Lanes Hart, 1879)109-110.

34. Scientific Society History and Roll. Found in the Charles Francis Himes Family Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, PA.

35. Charles Francis Himes, A Sketch of Dickinson College. (Harrisburg, PA: Lanes Hart, 1879)109-111.

36. Charles Francis Himes, A Sketch of Dickinson College. (Harrisburg, PA: Lanes Hart, 1879)112.

37. Manuscript of Autobiography of Charles Francis Himes. Found in the Charles Francis Himes Family Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, PA.

38. Charles Francis Himes, A Sketch of Dickinson College. (Harrisburg, PA: Lanes Hart, 1879)120.

39. Manuscript of Autobiography of Charles Francis Himes. Found in the Charles Francis Himes Family Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, PA.

40. Charles Francis Himes, A Sketch of Dickinson College. (Harrisburg, PA: Lanes Hart, 1879)120-122.

41. Dickinson College Catalogue 1866-1875. 1866 edition.

42. Charles Francis Himes, A Sketch of Dickinson College. (Harrisburg, PA: Lanes Hart, 1879)123.

43. Dickinson College Catalogue 1866-1875. 1867 edition.

44. Scientific Society of Dickinson College Rules and Regulations. Found in the Charles Francis Himes Family Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, PA.

45. Scientific Society of Dickinson College Rules and Regulations. Found in the Charles Francis Himes Family Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, PA.

46. Scientific Society of Dickinson College Rules and Regulations. Found in the Charles Francis Himes Family Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, PA.

47. Scientific Society of Dickinson College Rules and Regulations. Found in the Charles Francis Himes Family Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, PA.

48. Charles Francis Himes, A Sketch of Dickinson College. (Harrisburg, PA: Lanes Hart, 1879)124-126.

49. Dickinson College Catalogue 1866-1875. 1871-1872 edition.

50. Dickinson College Catalogue 1870-1880. 1877-1878 edition.

51. Dickinson College Catalogue 1880-1890. 1885 edition..

52. Dickinson College Catalogue 1880-1890. 1885 edition.

53. Dickinson College Catalogue 1880-1890. 1886 edition.

54. Charles Francis Himes, A Sketch of Dickinson College. (Harrisburg, PA: Lanes Hart, 1879)130.

55. James Henry Morgan, Dickinson College 1783-1933. (Harrisburg, PA: Mount Pleasant Press, 1933)348.

56. Charles Francis Himes, A Sketch of Dickinson College. (Harrisburg, PA: Lanes Hart, 1879)131.

57. Charles Francis Himes, A Sketch of Dickinson College. (Harrisburg, PA: Lanes Hart, 1879)131.

58. Charles Francis Himes, A Sketch of Dickinson College. (Harrisburg, PA: Lanes Hart, 1879)132.

59. Pamphlets of the History of Dickinson College. Found in the Charles Francis Himes Family Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, PA.

60. Pamphlets of the History of Dickinson College. Found in the Charles Francis Himes Family Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, PA.

61. Pamphlets of the History of Dickinson College. Found in the Charles Francis Himes Family Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, PA.