Himes

began his interest in photography when he was only twenty years old

(1858). Two years later, his friend, Joseph M. Wilson instructed Himes on

how to make fern and leaf prints.

Himes

began his interest in photography when he was only twenty years old

(1858). Two years later, his friend, Joseph M. Wilson instructed Himes on

how to make fern and leaf prints.Catching a Glimpse for Forever

by Christine L. Line

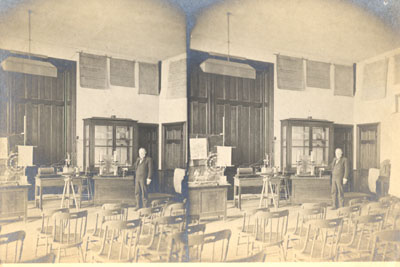

When visiting Dickinson College and seeing the name Charles Francis Himes, if you recognize it you may acknowledge him as a scholar, professor and former President of Dickinson. However, while all of these are true, few know of his extensive interest in photography. This interest grew to allow Himes the wherewithal to offer advice and counsel on various facets of the science. Himes, while considering himself an amateur, was a leader in the field of photographic development, technique and education. In Himes' collection in the Dickinson College Archives, there are detailed journal articles and pamphlets both authored by Himes and others. These scholarly articles elaborate on new photo developing techniques and new findings in photo experimentation regarding preservation of the image. Also found in the collection are over four hundred photographs, presumably taken by Charles Himes, in various subject areas; documents, views and portraits name only a few. These photographs were taken with more reason than just recreational pursuits, Himes used his new interest as a means of preservation. Whether is was documents, buildings, or people, Himes knew that a well kept photograph would out last many of the images themselves.

Himes

began his interest in photography when he was only twenty years old

(1858). Two years later, his friend, Joseph M. Wilson instructed Himes on

how to make fern and leaf prints.

Himes

began his interest in photography when he was only twenty years old

(1858). Two years later, his friend, Joseph M. Wilson instructed Himes on

how to make fern and leaf prints.

Some similar prints are found in the photo collection. This instruction was only the beginning of Himes' understanding of photography. He went to great lengths to become learned in this subject. Often, Himes would ask advice from colleagues and mail order catalogues in order to develop better understandings of what were the best developing techniques. In several personal journals, Himes refers to different experiments and records chemical recipes of development solutions. His practice led him to great reputable status among amateur photographers and scientists alike as he brought the camera and photograph closer to society's grasp.

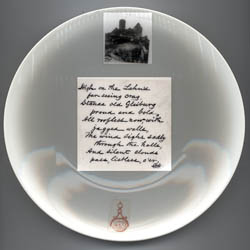

The fascination

Himes had with photography was not one of mere sport. Himes was a

scientist, but this aside, he was also a preservationist. Many of his

experiments revolved around his concern of how to make an image last the

longest. Himes not only used paper as his palate; he used tin, and ceramic

tiles to adhere images as well, with the belief that they would outlast

paper. One item unique to the collection is a ceramic plate bearing a

picture of a castle and a poem.

poem.

The poem reads:

The poem reads:

High on the Lahn's / Far seeing crag,

Stands old Gleiburg / Proud and bold.

All roofless now with / Jagged walls,

The wind sighs sadly / Through the halls,

And silent clouds / Pass, listless, o'er.

This

piece shows the enjoyment Himes took in his work. In preserving an image

of a crumbling castle he records a poem in its memory. His photograph of

the castle and his poem is an acknowledgment his to preserve the things which he

knows will not last forever. While few images have the privilege of

bearing Himes' poetry, they speak volumes of his interests. A large

portion of the photographs in the Dickinson collection are those of family and

friends, German towns and Dickinson College buildings. However, some of

the most interesting photographs are those of letters and documents. In

the collection there are documents regarding endorsements of different

contracts, as well as, letters signed by Benjamin Franklin and George

Washington. This is particularly fascinating because although Himes does

not outwardly acknowledge a particularly strong interest in these individuals,

he photographs their letters as a way to preserve and protect them for years to

come. In a sense, Himes used the camera as we use our twentieth century

copy machine, computer scanner and Internet. Himes' use of the photograph

not only captured the image but it made it more readily available to more than

one individual at a time, if duplicate copies were made. He used the

method of duplication as a teaching tool as he could photograph texts to

students where use of the printing press would have been inefficient.

Also, Himes created a unique marketing tool for the benefit of Dickinson

College. He wrote a history of the college and included photographs of the

buildings on campus. This could then be mailed anywhere around the world

to give individuals a

more than

one individual at a time, if duplicate copies were made. He used the

method of duplication as a teaching tool as he could photograph texts to

students where use of the printing press would have been inefficient.

Also, Himes created a unique marketing tool for the benefit of Dickinson

College. He wrote a history of the college and included photographs of the

buildings on campus. This could then be mailed anywhere around the world

to give individuals a glimpse of what they could learn at Dickinson. His

usage of the photograph was far more revolutionary than people give him credit

for. His actions created new benchmarks for society as he continuously

raised the expectations of this new instrument. As a professor of sciences

for the college, Himes naturally took interest in sharing his knowledge of

photography with his students. His desire to educate on this subject

extended far beyond the College campus.

glimpse of what they could learn at Dickinson. His

usage of the photograph was far more revolutionary than people give him credit

for. His actions created new benchmarks for society as he continuously

raised the expectations of this new instrument. As a professor of sciences

for the college, Himes naturally took interest in sharing his knowledge of

photography with his students. His desire to educate on this subject

extended far beyond the College campus.

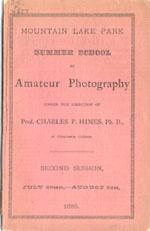

In an effort to bring more awareness to photography, Himes obtains permission, from the park authorities, to open a summer school for amateur photographers at Mt. Lake Park, Maryland in 1884. This school developed overwhelming interest in photography from men, women and children alike. It was one of the first schools of its kind and taught the applicants what they would otherwise be unable to learn; due to the cost of the equipment, materials and naivety of proper procedure. The purpose of the school, from the handbook, reads:

The wide range of scientific facts and principles involved in the practice of photography and the numberless applications that bring it into contact with every one, give it an education value of its own, but the recent advances have so simplified its processes and reduced the number of necessary operations and consequent trouble and expense, the Photography has rapidly taken the position of the leading, it might almost be said fashionable, amateur art.

While

the object of this school was to educate, Himes made it clear that this art

carries with it numerous applications. His course catalogue can appeal to

even the most novice of amateurs as he will instruct in the "Blue Printing

Process," the "Silver Printing Process," the "Negative

Process with Wet Collodion, for Production of Negatives by the Camera," and

for a more talented amateur, the "Dry Plate Negative Process."

Students can be assured also that they are learning the most recent possible

process for developing, "Attention will also be called to recent advances

in photography and to new processes and applications." Himes takes

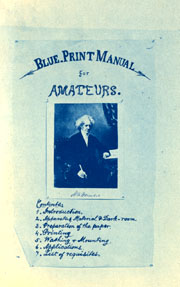

this matter very seriously, so much that he makes an instruction manual,

"Blue Print Manual for Amateurs," exclusively

out of photographs. His text is typed and photographed then pasted in book

fashion to show the many uses of

While

the object of this school was to educate, Himes made it clear that this art

carries with it numerous applications. His course catalogue can appeal to

even the most novice of amateurs as he will instruct in the "Blue Printing

Process," the "Silver Printing Process," the "Negative

Process with Wet Collodion, for Production of Negatives by the Camera," and

for a more talented amateur, the "Dry Plate Negative Process."

Students can be assured also that they are learning the most recent possible

process for developing, "Attention will also be called to recent advances

in photography and to new processes and applications." Himes takes

this matter very seriously, so much that he makes an instruction manual,

"Blue Print Manual for Amateurs," exclusively

out of photographs. His text is typed and photographed then pasted in book

fashion to show the many uses of photography. For a minimal cost, the

two-week school provides unending possibilities for those in attendance.

In an effort to create return members, Himes created the Mountain Lake Park

Photographic Exchange Club. Anthony's Photographic Bulletin reports

that the turnout of the second annual convention was good as members came from

Philadelphia, Baltimore, Martinsburg, Wheeling and Cumberland.

photography. For a minimal cost, the

two-week school provides unending possibilities for those in attendance.

In an effort to create return members, Himes created the Mountain Lake Park

Photographic Exchange Club. Anthony's Photographic Bulletin reports

that the turnout of the second annual convention was good as members came from

Philadelphia, Baltimore, Martinsburg, Wheeling and Cumberland.

In 1889 Himes delivered a speech to the Franklin Institute titled "Amateur Photography in its Educational Relations." Himes' "case study analysis" is his experience teaching photography at Mt. Lake Park. He notes that the definition of amateur can be twofold, he defines it as "by amateur photography then this evening we mean amateur practice, whether by professional or non-professional." This statement makes it clear that regardless of age or status, one can always be educated since they are merely "amateur." Further on in the lecture Himes gives his reason for teaching photography:

Photography presents many features that led me to adopt it as a laboratory exercise many years ago, and to retain it at present in the physical laboratory as a valuable educational means. It is recommended by the wide range and varied character of its operations, from the simple blue print to the highest scientific applications, as well as by the progressive character that may be given to its exercises. In common with many other minor arts, its results are things, not simply facts. They can speak for themselves, and are in the main permanent, can be referred to at any time, and are comparable with subsequent results.

The fact that he consistently remains concerned with results shows that he is adamant about forward progression. His lecture closes with descriptions of the courses he offers at Mt. Lake Park and he recalls different students that present questions for his answering. One such case regards his instruction of a twelve year old girl when she complains of not taking pictures correctly, "I have written her frankly that it is not the camera that take the picture, but the little girl behind it."

Himes' use of Mt. Lake Park extends beyond the instruction of student amateurs. The magazine Photography reports on behalf of the The Society of Amateur Photographers the minutes of the "Fifth Annual Convention of the Photographers' Association of America." Mr. Wilson of Philadelphia notes:

The next thing I have is a letter of invitation. It is written to Professor C. F. Himes, one of our oldest amateurs, and who is to-day conducting a school of photography at Mountain Lake Park, Maryland. The letter is from Charles R. Baldwin, President of Mountain Lake Association. The letter is an invitation for the association to hold its session of 1885 at Mountain Lake Park.

This invitation would certainly come as a great compliment to Himes. It recognizes that his school is an environment suitable for discussions, lectures and meetings on photography, not just a place for students to take pictures. It is not surprising that Himes became such a reputable figure in the field of Photography. Seldom to individuals put as much energy into self-education of the art let alone the education of others.

Himes' reputation exceeded his association with Mt. Lake Park. Among professional photographers he was viewed as an expert resource in the mechanics of photography. Himes authored several articles and pamphlets on the chemical and physical techniques in photography. However, he returns to the concern of his product, the photograph. In an address Himes gave in 1902, he relates this concern:

Time has in very many cases, then, doubtless been made the scapegoat for many avoidable causes of photographic deterioration, for imperfect knowledge or oversight of conditions, for unscientific or careless work, for imperfect treatment and storage, etc. The survival of one specimen in excellent condition is sufficient to establish permanence of any method, and direct investigation to the causes of deterioration with certainty of success in discovering and combating.

Himes

continues to mention that several colleagues have developed methods of

developing photographs that undoubtedly make them last longer than other

methods. Also, he stresses that by simply keeping the photographs in a dry

place creates an environment where they can be preserved; one case states for

over thirty years.

Himes

continues to mention that several colleagues have developed methods of

developing photographs that undoubtedly make them last longer than other

methods. Also, he stresses that by simply keeping the photographs in a dry

place creates an environment where they can be preserved; one case states for

over thirty years.

Himes' quest for preservation and permanence carries through the summers in Maryland back to his career at Dickinson. In the opening address of the Jacob Tome Scientific Building, Himes addresses the crowd with great enthusiasm, relating his great love of education:

We stand to-day at the transition form the old to the new. Behind us more than a century of achievement, before us the grander possibilities of the unlimited future; not separated from each other by the imaginary line of a closing century, but by what is more substantial and easily recognized, a beautiful building with broad and deep foundations.

He goes on to mention photography. He recalls how it took the nation by surprise with the ability to capture a human portrait. And how now, it is so common that it is difficult to avoid. He relates that teaching science is not simply a "mass of facts." "Some may consider a building a good advertisement for a college, and so it may be; but in education it is no better policy, than in mercantile pursuits, to advertise wares different from furnished." His uncanny return to education should not come as a surprise, for it is who he is. In the closure of the address, Himes makes a broad statement:

A live teacher will always have the spirit of the investigator, or he will soon deteriorate into a mechanical teacher, lose caste among his fellow workers and should be called upon to make way for some on more efficient. I trust that New Dickinson will not fail to take her proper place in the journals that record the progress of science for want of anything that money can supply, or for want of that modicum of time for investigation, that every teacher should have, form the spent in instruction.

It is difficult to distinguish the fact that Himes is speaking of those other than himself, however, clearly he speaks from experience. His quest to understand photography gave him another source from which to educate on the importance of this instrument as a gateway into the future. A talent he expressed here and around the world. He would go to all extremes in order to meet the challenge, "Day by day, year after year has it been necessary by personal labor and sacrifice to supplement limited provision for educational demands." Today we are the ones who reap the rewards of Himes' great desire to fulfill his quest for better understanding as we have the privilege of examining his years of experience.

Works Cited:

Chicago Amateur Photographer's Club. Photography. Sept. 1, 1884. Found in the Charles Francis Himes Family Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

Himes, Charles Francis. Amateur Photography in its Educational Relations. Reprinted from the Journal of the Franklin Institute. May 1889. Philadelphia. Found in the Charles Francis Himes Family Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

Himes, Charles Francis. Jacob Tome Building Address. June 24, 1885. Harrisburg, PA. Found in the Charles Francis Himes Family Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

Himes, Charles Francis. Mountain Lake Park Summer School 'Amateur Photography.' July 1885. Found in the Charles Francis Himes Family Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

Himes, Charles Francis. Photographic Permanence and the Amateur Photographic Exchange Club 1860-64. Reprinted from the Journal of the Franklin Institute. May 1902. Philadelphia. Found in the Charles Francis Himes Family Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

Mountain Lake Park Photographic Exchange Club. Anthony's Photographic Bulletin. Found in the Charles Francis Himes Family Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

Vodra, Stacie L. Charles Francis Himes: Portrait of a Photographer. Cumberland County Historical Society. Vol. 14, No. 2. Winter 1997. Carlisle, PA.