A Youth in the Wild:

Charles Francis

Himes in Kansas Territory

by LeAnn Fawver

After

graduating from Dickinson College in 1855, and briefly teaching school

in Pennsylvania, Charles Francis Himes ventured Westward. Charles

Himes traveled through Ohio on his way to Chicago, Illinois. In Ohio

he found the new homes to exactly fit his taste, “pleasing to the eye”

despite the “monotonous scenery.” Himes was also impressed with the

successful speculation of his good friend Martin Deal. In a letter to his

mother on September 29th, 1856, Charles admitted that Mr. Deal had offered

to set him up in some business, but that he wanted farther west.

His hopes were openly pinned on Kansas or Nebraska Territory, dependent

on the results of the upcoming election. If Fremont, the Republican

candidate in 1854 and again in 1858, had claimed the presidency, Himes

intended to make for Kansas. In case of a Republican failure, Charles

was prepared to settle for Nebraska. But he wrote, “I take it for

granted Fremont is to be the next President.”1

Himes did

indeed venture further West, but not immediately for Kansas. During

the autumn and winter of 1856-57, Charles Himes taught school in Illinois,

an experience from which he would judge all later travels in the Western

United States.

While

Himes was still completing his Bachelor’s degree at Dickinson College,

larger events were occurring. In 1854, the United States Congress

passed the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which organized the two respective territories.

This was done for a variety of reasons, partially because settlers were

already ‘squatting’ in both territories and also to open the route for

a transcontinental railroad across the middle of America. As an added

bonus, the Kansas-Nebraska Act would also be the testing grounds for a

popular sovereignty.

All

previous Western Territories had the issue of slave state or free state

decided for them by act of Congress. This created a string of compromises

such as the Missouri Compromise that prevented the spread of slavery north

of latitude 36o, 30’. In the process, a delicate balance

was created and maintained between the slave states and the free states.

A rough power equality between the two parts of the United States ensured

the survival of the nation and the institution of slavery.

But

the new doctrine of Popular Sovereignty, introduced by Stephen Douglas

in his famous debates with Abraham Lincoln, overturned all previous compromises

made by Congress. Instead the issue of whether to be a slave state

or a free state would be decided upon by the citizens of Kansas and Nebraska

Territories. Whichever side achieved a majority before the territories

gained enough population for statehood would determine not only the futures

of the territories, but also of the balance of political power in the United

States Congress.

Southern

settlers easily flooded Kansas Territory with slaves in tow. Other

southerners took advantage of the fresh territory to expand their opportunities

and possibly to enhance their social standing. Northern groups, among

them the Abolitionists, were not to outdone. They formed emigrant

aid societies to recruit and support settlers. Both groups indulged

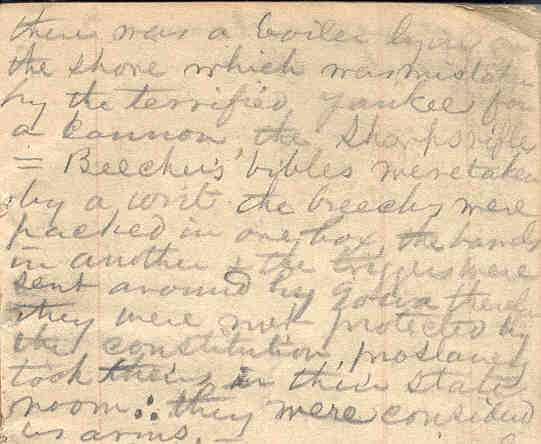

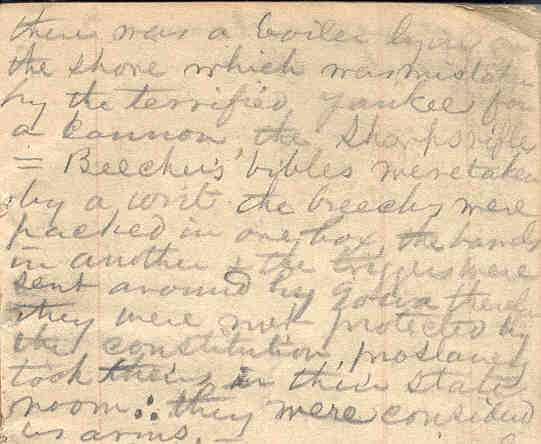

in truly vicious politics. When the vicious politics between pro-slave

and pro-free turned into open violence, the Northern emigrant aid societies

shipped special ‘supplies’ to Kansas Territory. Laws prohibited the

transport of arms and ammunition into the troubled territory. To

escape this prohibition, emigrant aid societies disassembled the riffles,

“…breeches were packed in one box, the barrels in another and the triggers

were sent around…therefore they were not protected by the Constitution.”2

The parts were then packed into boxes labeled as Bibles. Both sides

of the conflict soon used the euphemism “Beecher’s Bibles” in recognition

of the heroine of the abolitionist cause. In the escalating violence,

the two competing groups destroyed whole towns. Adding to the confusion

and bloodshed, Missouri residents, called Border Ruffians, flooded across

the Kansas border to vote illegally in the territorial election.

The eyes of the nation focused on “Bleeding Kansas,” a prelude to the showdown

between free and slave.

By 1857,

the bloodshed and confusion had abated, somewhat, due to government intervention.

Settlers still entered the territory seeking opportunity. Land speculation

ran rampant. But although the open violence had declined, pro-slave

and pro-free still held one another in deep-seated animosity. Pro-slave

and pro-free had by this time established two separate governments, each

one claiming to be the legitimate government of the territory. Lecompton

housed the slave-state government, officially recognized by the Congress

of the United States. Meanwhile the free-state government met in

Topeka to pen its own constitution. A federally appointed territorial

governor desperately tried to maintain peace in Kansas.

Illinois

in 1856 had not met with Charles Francis Himes’ approval. He found

the people disagreeable. According to his 1857 journal, the people

in Illinois could not “…pass you without insulting you”. Added

to their poor manners, Himes found Illinois to be a poor country for a

traveler with a “lank purse.”3 Disappointed in Illinois

by both its inhabitants and its expense, bored with teaching, longing for

something exciting and profitable, Himes was convinced by a companion to

try for Kansas Territory.4

His

adventure began in January. Charles ventured from his ‘brick school

house’ in Illinois to Keokuk on foot over the frozen Mississippi River.

In the same January letter, Himes mentions a potential guide to investing,

one William Lynch.5 Stuck in Illinois by poor weather,

Charles affirms in a letter to his father that William Lynch is the only

man he trusts in regards to Kansas lands.6 A February

1857 letter from his father cleared the funds necessary for Charles Himes

to travel to Kansas with the intent to invest in land.7

Charles

Francis Himes’ travel journal takes up the story throughout the month of

March and into April of 1857. Himes traveled along the Mississippi, which

he described as “very monotonous and ... tedious,”8 to

Rocheport, then through Booneville and Glasgow, “quite flourishing places

on the Missouri.”9 From Glasgow Himes paid a livery

service to travel to Fayette, Missouri on March 8th, 1857. Charles

was then delayed again by foul weather.

For a few

days, Himes explored the towns of Fayette and Glasgow, visiting acquaintances

and school buildings. He was “well pleased” by a Mr. Pritchett’s

school for men. Himes also visited the female department of Howard

High School. There he attended a class in Ray’s Arithmetic Third

Part, led by Mr. Lucby at the female college. Charles Himes

considered the girls at this school to be “…the best drilled girls [he]

ever saw.”10 Neither town had a “a dram shop or

a place to get liquor” as a cure for the insufferable cold weather.11

His experiences

in Fayette with some of the 6,000 slaves in Howard County ‘mollified’ “any

prejudices [he] had to[wards] slavery…in a great degree by witnessing the

practical workings of the system.” On the evening of March 9, 1857,

Himes spoke with an unnamed group of citizens on the question of slavery.

According to Himes, the group was very moderate on the question of slavery

with “some admitting it [slavery] was a political curse to the white man.”12

March 13th

dawned with the arrival of a steamboat, The Morning Star at Glasgow.

For four dollars and fifteen cents, Himes bought his initial passage and

ten additional dollars to Kansas City. The “first thing [he] saw

was a table full of money with gamblers around.”13

Himes traveled by this crowded steamboat along the Missouri River to Brunswick,

Waverly and Thomas, past the ‘small place’ of Berlin and Lexington, then

finally to Wayne City.

During a brief

stop at Brunswick, the terrified Yankee passengers mistook an old boiler

lying on its side on the shore for a pro-slave cannon, perhaps in retaliation

for the “Beecher’s Bibles” of the abolitionists. After Lexington, an “old

Kentuckian” boarded the ship, and gave all aboard “a fine time on the slavery

question.” Later, a Kansas judge came on board. While

this judge spoke with a Virginian, he appeared cheerful on the prospects

of Kansas entering the union as a slave state. Apparently the official

government (pro-slave) had recently passed a law that would prohibit the

Free State men from gaining the necessary qualifications to vote until

after the November election. In between political discussions, passengers

played cards, and sang songs. The gambling on board ship disgusted Charles

Himes, who could not play cards “when [he saw] gambling going on.”

Charles Francis Himes lamented in his diary that steamboat travel “would

be grand” but for the lack of “good company.” He slept on the floor

until he managed to steal a cabin berth that was not much improvement on

the hard floor, but at least slightly warmer.14

In 1857 Wayne

City was a small landing “liable to wear and tear.” From there on

March 15th, Himes went to Kansas City and Westport. He spent the

15th and 16th dividing his time between these two cities.15

Not finding

William Lynch in Kansas City, Himes hired a hack to Westport. True to his

previous occupation, Charles visited the brick school building. There

he met with Mr. Tom Johnson of the Mission Schools, whose lack of courtesy

Himes’ attributed to a suspicion that Charles was a "free stater."

Mr. Johnson said they were of a National Party “because that [pro-slavery]

was sectional.” Johnson supported the federally appointed Governor

Geary for doing as well as any man could under the divided circumstances

of Kansas Territory. For all his political views, Mr. Johnson did

suggest Council Grove as a likely spot for speculation as “…they are just

laying out a town.”16

Of the town of Westport, Charles

Himes found it to be “…a fine large town…” with a “…very lively general

stage depot…” that connected the town “…to all parts of the territory.”

Many emigrants passed through Westport. It was in the words of Charles

Francis Himes, the “most business looking town [he] saw”. Adding to the

local flavor, during his return trip to Kansas City, Himes saw “some pretty

squaws”. He would also see “real live wild Indians” in Kansas

City proper. They appeared to Himes as “a mean squalid filthy

looking set.”17

According

to Himes, Kansas City was “a largely laid out place…finely situated about

1 7/8 miles from the mouth of the Kansas River.” Furthermore, “it

is built on very rough ground,” but possessed a levee which Charles thought

to be permanent. There was only one rooming house fit for Charles

Francis Himes, the America House kept by the Chiles. Better residences

were located on the outskirts of the city. The interior had many

scattered buildings, and lots with already inflated prices. Himes

wrote of on March 16th, 1857, that he felt “…like going to Missouri and

setting down to teaching, leaving this hum bug country.”18

Anxious to

meet with Lynch and begin his land speculation or simply to leave Kansas

Territory, Charles Himes boarded a steamboat again (this time the Cataract)

to Leavenworth, thirty-six miles away, on March 17th, 1857.

During the trip Himes saw Lieutenant Governor Roberts and Governor Robinson

of the pro-free government. The Cataract passed Parckville, where the press

was thrown in the river during the violence. That night the weather

was “very, very cold.” The steamboat ran out of wood and coal, and

all the fires on board extinguished from lack of fuel. To restart

the boat and prevent frostbite, the crew had to salvage wood from a fence.

The poor living conditions and bad weather contributed to Himes catching

“a very heavy and alarming cold.”19 Finally arriving at

Leavenworth, the steamer was met at the docks by a “great crowd.”

Two hundred and forty passengers joined the throng, including Charles Himes.

After enduring such a passage, Himes as no doubt disappointed when he failed

to find his prospective partner in Leavenworth. William Lynch had

left for the interior several days before Himes’ arrival.20

Leavenworth was a bustling town.

Many of the buildings were “transient wooden affairs to do business in.”

Himes decided against investing in Leavenworth, for a sediment bar was

forming at the landing that “may become a serious obstruction to trade.”

While in Leavenworth an acquaintance named Ralston informed Himes that

the Topeka (Free) convention had resolved not to vote in the upcoming election,

thereby undermining the Slave Government’s ability to claim popular sovereignty.21

Himes returned

to the search for William Lynch; he traveled to Weston by road with a Mr.

Ward, Barker, Bealle and company. Together they pushed on through

muddy roads on March 19th to St. Joseph, Missouri. The poor roads

forced the intrepid travelers to take lodging for the night a mere five

miles from their destination.

St. Joseph

was “a fine growing place of about five thousand people.” It was

situated on a bluff, and surrounded by “very good land, especially for

hemp,” used in the production of rope. The town expected a railroad

from Hanibal, Missouri to be completed in a year. Consequently this

boomtown had lots for sale for two hundred dollars per square foot.

Before starting on the road, Himes visited “several academies.”22

Himes

and a companion named Robinson hired a hack and started for Fillmore, then

to Savanna.23 In Savanna, Himes met a mutual acquaintance

of Israel Deal, in California. Through talking with this gentleman

Charles Himes admits to his diary, that he “got slightly touched with California

fever.” By Saturday, the 21st, Himes was on the move again.

He stopped again at Fillmore with the intent to rest for a week.

There a Mr. McCauley, the district schoolteacher, gave Himes “a woeful

account of his winter’s trials.” Rain further delayed him.

On April 4th, Charles and another friend tried for St. Joseph on a "whim."24

To accomplish

their trip, the two desperately sought some means of transportation.

Finally they succeeded in hiring a horse and a mule. Charles kind

friend allowed him to take the horse, and no amount of persuasion would

change his friend’s determination to ride the mule. The pair set

off at eleven o’clock, having dubbed their trusty mounts, Dapple (the mule)

and Rosinante (the horse) after the mounts in Don Quixote. Unbeknownst

to Himes and friend at the time, their ‘apparently gentle’ mule had thrown

a boy twice. Neither animal would move faster than the slowest walk

unless constantly prodded by their riders, and would stop completely should

any other animal pass by them on the road to the "mirth of many" other

travelers.

Their

stubborn mounts also feared the many large mud puddles in the road, fearing

that they were traps of some sort. At one point on the road, Charles

reports that they had to force their mounts in to the mud, which reach

to the belly of Charles’ horse. About four and half outside of Savanna,

Himes found himself five paces ahead of Dapple, the mule, when he heard

a bizarre noise, which Charles describes, “such as a whale is accustomed

to make when it finds itself suspended in mid air by hook and line.”

Dapple started to buck with the intention of ridding himself of the cumbersome

human in the saddle. Himes barely controlled his own mount, and holding

tight to the harness, leapt off the horse. Meanwhile the mule “scampered

past...with the saddle on his heels.” This was too much for the startled

horse that shook its reins lose from Himes and ran with his fellow escaped

mount. Charles Himes and friend were left in the animals’ dust, to

gather their “scattered paraphernalia and [chase] the animals over the

plain, amid the underbrush, through the forest, and finally into a stable”

of one Mr. Pixler.25 Mr. Pixler provided entertainment

and dinner for the tired young men, but would not go near the mule.

Nor would Mr. Pixler allow any of his stable boys near it. Himes

and friend were forced to care for the stubborn animal themselves.

They prudently chose to walk to Savanna that night.

However

the next day, Himes and friend again tried their luck with the mule and

horse pair. Himes’ horse was restless. Apparently he was so

occupied with his own mount that he did not notice his friend’s absence

until arriving for dinner in Fillmore. Charles ran to find his missing

friend. Half a mile outside of Fillmore, Charles’ friend was again

pitched from his mule, which then tried to return to Savanna!26

(After this amazing tale, the journal becomes illegible.)

After

his adventures in Kansas Territory, Himes ventured to Missouri. In

a letter to his father written on May 10, 1857, that he had waited for

news from home before starting for something in the “Purchase.” However

his delay, coupled with foul-traveling weather stopped his aspirations

in that direction. Himes also admitted his failure to catch William

Lynch, a friend who had promised to aid his efforts towards land speculation.

To reassure his father, Himes predicted that Kansas land prices would drop

in the autumn and that he would buy then, perhaps even lay out a town in

Southern Kansas Territory.27 By June 7th,

Himes and another partner had purchased some land in Missouri instead of

Kansas. In order to make use of himself in the meantime, Himes took

work as a schoolteacher in St. Joseph.28

Despite

his desire to head further West, Charles Himes was torn by conflicting

desires. A letter of August 12th sought advice from his father.

Should Charles venture further West, farther from the heart of his family?

Or should give up the young man’s folly of the West and return to the East?

Wherever Himes decided to go, what then should he do with his life?

Is the study of law or the start of a business better suited to a man such

as Charles Francis Himes?29 Earlier letters from

home offered no solutions. William Himes wrote to his son in May

1857. He begged his son to “engage in something permanent or come

home”, claiming that his sons’ much traveling about worried him.

The elder Himes continued, in the letter, to warn his son against the dangers

of speculation.30

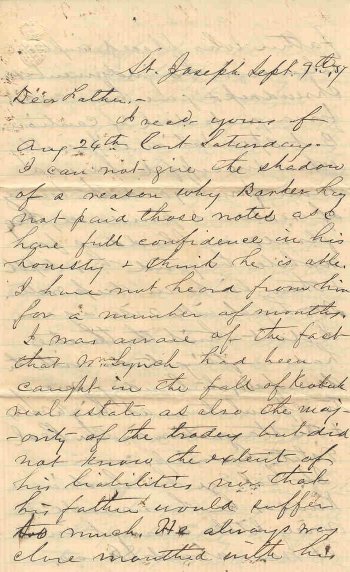

Himes’

prediction of a fall in land prices came true during the month of September

1857, but differently than he imaged. His acquaintance, William Lynch,

was apparently caught in the fall of Kansas land prices in early September.31

By mid-October, a complete Panic had reached Missouri land speculators.

He reported in a letter to his sister, Helen, that there had not yet been

any sales or bank failures. However bank bills were no longer acceptable

as cash! Cheering the expulsion of ‘paper towns’ from the territory

of Kansas, Himes predicted confidence to return soon.32

Two weeks later October 23 found Charles Himes closing his school for the

harvest season while the Panic continued. Himes, perhaps only to

reassure his sister, insisted that his town lots were safe. But he

does admit that his partner was panicking.33

Ironically

this same letter contains news of his intent to return home to New Oxford.

A November 2nd letter, again to Helen, describes his planned route home.34

For all the problems Charles Francis Himes endured in the West, he admitted

in his letter that he almost stayed. Another school had offered him

a position, and he had “hoped to accomplish something” in the West.

Instead Charles Francis Himes returned to the East, and a position teaching

school which his father had found for the young traveler.

After returning

to the East, Charles Francis Himes briefly taught school at a female college

in Baltimore, Maryland. Himes later became a science professor, which

eventually took him back to Dickinson College. Charles Himes revolutionized

the teaching of science in a liberal arts school by instituting a system

of laboratory work. Under his leadership, science became a major

component of a Liberal Arts Education.

Charles Himes

ventured West along with millions of other Americans. But he was not alone

in the decision to return to the East. Why Charles Himes decided

to return to the East is unclear. Was he unhappy surrounded by the

conflict over slavery? Did the Land Speculation Panic destroy his

hopes of profit, or did his father refuse to sponsor further unstable investments?

Unfortunately, the reason will remain unclear until further research has

been made into the Western Travels of Charles Francis Himes.

1 Himes, Charles Francis, Letter to Magdalen Lanius Himes, September 29, 1856. Found in the Charles Francis Himes Family Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

2 Himes, Charles Francis, Diary 1857 (transcript), 2. Found in the Charles Francis Himes Family Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

3 Himes, Charles Francis, Diary 1857 (transcript), 1. Found in the Charles Francis Himes Family Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

4 Himes, Charles Francis, Letter to William Daniel Himes, January 13 and February 9, 1857. Found in the Charles Francis Himes Family Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

5 Himes, Charles Francis, Letter to William Daniel Himes, January 13, 1857. Found in the Charles Francis Himes Family Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

6 Himes, Charles Francis, Letter to William Daniel Himes, February 9, 1857. Found in the Charles Francis Himes Family Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

7 Himes, William Daniel, Letter to Charles Francis Himes, February 11 and 21, 1857. Found in the Charles Francis Himes Family Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

8 Himes, Charles Francis, Diary 1857 (transcript), 1. Found in the Charles Francis Himes Family Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

9 Himes, Charles Francis, Diary 1857 (transcript), 1. Found in the Charles Francis Himes Family Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

10 Himes, Charles Francis, Diary 1857 (transcript), 1. Found in the Charles Francis Himes Family Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

11 Himes, Charles Francis, Diary 1857 (transcript), 2. Found in the Charles Francis Himes Family Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

12 Himes, Charles Francis, Diary 1857 (transcript), 1. Found in the Charles Francis Himes Family Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

13 Himes, Charles Francis, Diary 1857 (transcript), 2. Found in the Charles Francis Himes Family Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

14 Himes, Charles Francis, Diary 1857 (transcript), 3. Found in the Charles Francis Himes Family Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

15 Himes, Charles Francis, Diary 1857 (transcript), 2. Found in the Charles Francis Himes Family Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

16 Himes, Charles Francis, Diary 1857 (transcript), 2. Found in the Charles Francis Himes Family Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

17 Himes, Charles Francis, Diary 1857 (transcript), 4. Found in the Charles Francis Himes Family Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

18 Himes, Charles Francis, Diary 1857 (transcript), 4. Found in the Charles Francis Himes Family Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

19 Himes, Charles Francis, Diary 1857 (transcript), 4. Found in the Charles Francis Himes Family Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

20 Himes, Charles Francis, Diary 1857 (transcript), 5. Found in the Charles Francis Himes Family Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

21 Himes, Charles Francis, Diary 1857 (transcript), 5. Found in the Charles Francis Himes Family Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

22 Himes, Charles Francis, Diary 1857 (transcript), 5. Found in the Charles Francis Himes Family Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

23 Himes, Charles Francis, Diary 1857 (transcript), 5. Found in the Charles Francis Himes Family Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

24 Himes, Charles Francis, Diary 1857 (transcript), 6. Found in the Charles Francis Himes Family Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

25 Himes, Charles Francis, Diary 1857 (transcript), 6. Found in the Charles Francis Himes Family Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

26 Himes, Charles Francis, Diary 1857 (transcript), 7. Found in the Charles Francis Himes Family Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

27 Himes, Charles Francis. Letter to William Daniel Himes, May 10, 1857. Found in the Charles Francis Himes Family Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

28 Himes, Charles Francis, Letter to William Daniel Himes, June 1, 1857. Found in the Charles Francis Himes Family Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

29 Himes, Charles Francis, Letter to William Daniel Himes, August 12, 1857. Found in the Charles Francis Himes Family Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

30 Himes, William Daniel, Letter to Charles Francis Himes, May 1857. Found in the Charles Francis Himes Family Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

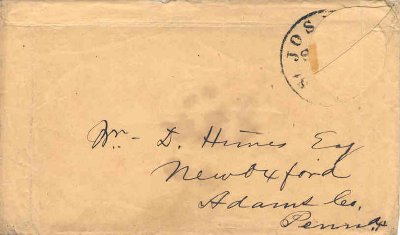

31 Himes, Charles Francis, Letter to William Daniel Himes, September 9, 1857. Found in the Charles Francis Himes Family Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

32 Himes, Charles Francis, Letter to Helen Anna Himes, October 14, 1857. Found in the Charles Francis Himes Family Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

33 Himes, Charles Francis, Letter to Helen Anna Himes, October 23, 1857. Found in the Charles Francis Himes Family Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

34 Himes, Charles Francis, Letter to Helen Anna Himes, November 2, 1857. Found in the Charles Francis Himes Family Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

Sources

Primary Sources:

Himes, Charles Francis.Diary 1857 (transcript).Himes, William Daniel.

Letter to Helen Anna Himes,

October 14, 1857.

October 23, 1857.

November 2, 1857.

Letter to Magdalen Lanius Himes, September 29, 1856.

Letter to William Daniel Himes,

January 13, 1857.

February 9, 1857.

May 10, 1857.

June 1, 1857.

August 12, 1857.

Spetember 9, 1857.Letter to Charles Francis Himes, February 11, 1857.

Letter to Charles Francis Himes, February 21, 1857.

Letter to Charles Francis Himes, May 1857.

Found in the Archives and

Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania.

Secondary Sources:

Nash, Gary B. and Julie Roy Jeffrey, eds. The American People:

Creating a Nation and a Society I. Addison Wesley Longman,

Inc. New York: 1998.

SenGupta, Gunja. For God and Mammon: Evangelicals and

Entrepreneurs, Masters and Slaves in Territorial Kansas,

1854-1860. The University of Georgia Press. London: 1996.

Gihon, John H. Geary and Kansas: Governor Geary’s Administration

in Kansas. J. H. C. Whiting. Philadelphia: 1857.

Hale, Edward E. Kanzas and Nebraska. Phillips, Sampson and

Company. Boston: 1854.