Rev. Raymond R. Brewer

Raymond R. Brewer graduated from Dickinson College in 1916. He then went to Drew Theological Seminary, though his stay there was interrupted by his service in the First World War as a chaplain. After the war, Brewer returned to Drew and there graduated in 1921 with a Bachelor of Divinity. Interested in missionary work, Reverend Brewer wrote to Dickinson College prior to his graduation to explore his options. In response to his inquiry, Dickinson College and the college YMCA used the funds they collected to support his travels to China as the newest missionary representative of the College, and, incidentally, Prof. Yost's replacement.1 He sailed for Shanghai on September 15, 1921.2

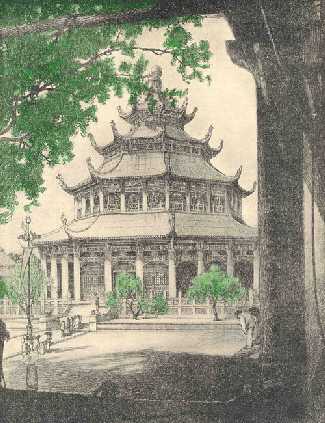

The Dickinsonian Supplement.

Mon. Nov. 20, 1916

Brewer's acceptance of the post at the West China Union University marked a significant shift in the missionary movement in China. Unlike Frank Gamewell, whose presence in China was paired with an air of superiority, however slight, Brewer seems to have looked upon his task as educating the Chinese about Christianity more so than converting them; "Education is power in China,"3is the statement that guided his actions over the years.

Through his many letters to the

Dickinsonian and faculty members

on campus, Brewer has left an interesting history of his impressions of

China and the West's relation to that nation. In one letter written

to the Dickinsonian prior to the 1924-25 fund campaign, and presented

to the student body in the article "Raymond R. Brewer Writes of Conditions

in China in Interesting Letter,"4Brewer

comments, in response to the growing concern over armaments in that country,

that China must be given time to "rid itself of the military mindset."

However, that the Dickinson College Extension Board could only raise about

$700 that year must reflect in some way the growing uneasiness with conditions

in China, despite Brewer's request for patience.

The Dickinsonian Supplement.

Mon. Nov. 20, 1916

(click on image for full size)

Around the same time as the 1924-25 China Fund Drive on the Dickinson Campus, various articles were circulating in China about the growing anti Christian movement. An example of the rhetoric the Chinese used in their attempts to discredit the religion was published in The Chinese Recorder in February of 1925:

We all know clearly that Christianity is a religion of superstition and vagueness which makes people more ignorant than the are...It is our duty to fight against this religion of imperial civilisation.5That same article in the Recorder delineates three causes for the recent disruptions:

May of 1925 would prove to be an inauspicious time for the foreign presence in China. In a series of letters to the Dickinson College Extension Board, Brewer explains the facts and his opinions on what came to be called the Shanghai Incident. On May 30, 1925, seventy student demonstrators were killed by British police in Shanghai. After this event, the Chinese distrust of foreigners, especially the British, reached new proportions. The fact that foreign investors made up a significant portion of the industry in Shanghai did not help matters much. The working conditions in the foreign run factories were poor at best, dangerous at worse, and the growth of Soviet propaganda in the area, while not enough to account for the state of unrest and aroused suspicions, was, according to Brewer, one of the contributing factors. Brewer suggested two things in response to this unhappy turn of events: one, that the nations with interests in China reevaluate their treaties out of respect for China and two, that Dickinson establish a weekly or biweekly forum on China so as to better inform students and to get their input. This enthusiasm for dialogue as a means of change would soon prove impossible, however.6

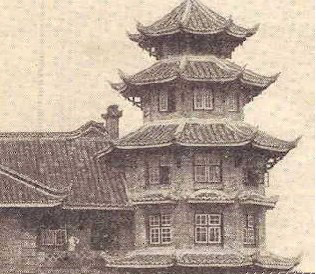

The Dickinsonian; Vol. XLIX,

No. 11, pg. 3

(for full version of photograph, click on image)

The November 11, 1926 issue of the

Dickinsonian reported that

the West China Union University had been temporarily closed by the Chinese

government due to the political situation.7

Encouraged to leave the country, as were all foreigners, Brewer returned

to the United States where he enrolled at the University of Chicago to

complete his graduate work. Though it was first reported that Brewer

would return to China once the political situation had stabilized, that

would not be the case.8 And, with

the closing of the West China Educational Union in 1929, his return became

a moot point.9 Little is

known about Brewer's activities following his tenure at the University,

and gradually, without his frequent letters and accounts of events, Dickinsonians

fell further away from their once heightened interest in China.

[top]

2. "College Extension in China Backed by Prominent Alumni." The Dickinsonian, Dec. 2, 1921. Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pa.

(To see a map of Brewer's path to Chengtu from Shanghai, click here.)

3. "China Campaign Opens Tomorrow with Meeting." The Dickinsonian, Dec. 2, 1921. Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pa.

4. "Raymond R. Brewer Writes of Conditions in China in Interesting Letter." The Dickinsonian, Nov. 10, 1923. Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pa.

5. The Chinese Recorder, Feb., 1925. Vol. LVI, No. 2. Dickinson-in-China, 1921-27; Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pa.

6. Letters from Raymond R. Brewer to the Dickinson College Extension Board. Dickinson-in-China, 1921-27; Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pa.

7. The Dickinsonian. Nov. 11, 1926. Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pa.

8. The Dickinsonian. Mar. 15, 1929. Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pa.

9. Report of the West China Union University to the Board of Governors. Aug. 1, 1929. Dickinson-in-China, 1921-27; Archives and Special Collections, Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pa.