The Boxer Uprising

The Boxer Uprising, or as it is more commonly known, the Boxer Rebellion,

began at the turn of the 20th century in the area south of Beijing.

What had begun as a somewhat disorganized harassment of Christians by poor

Chinese farmers in the early 1890s, soon became an organized movement of

thousands, and those thousands came pouring into Beijing, disrupting the

national capital and provoking the foreign powers that were stationed there

in the economic and political sectors.

The name "Boxer" is derived from the rituals performed by the adherents of a secret Chinese society, called I-ho ch'üan, or "Righteous and Harmonious Fists." Believing that their ritual gave them supernatural powers, they sought to end the privileged position the Ch'ing dynasty had given foreigners in their country; the means by which they sought their end led to the destruction of the dynasty itself.

At first the Boxers were both anti-foreigner and anti-dynasty, wanting not only the expulsion of all non-Chinese nationals but also the end of the Ch'ing dynasty, at the time ruled by the dowager empress, Tz'u-hsi. As the incidents related to the Boxer movement continued to escalate, so did the dynasty's interest in it. Once denounced by the official Chinese government, the Boxer Uprising was soon consolidated by the Empress Dowager as a means to gain popular support. The local municipalities, which previously had been ordered to halt any Boxer disturbance, soon were told to give the Boxers a free hand in their actions.

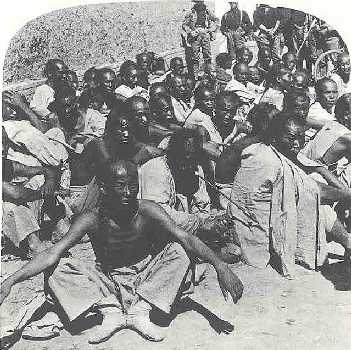

Also, the groups against whom the Boxers fought exacerbated the problem by their total dismissal of Chinese religion. Many of the missionaries that came to China at the end of the 19th century treated the Chinese in their own land much like they were treated in America, as second-class people, heathens who were in desperate need of Christ in their lives. Such an ethnocentric approach from the Westerners, coupled with the liberties taken by the foreign powers that had economic houses in the major cities, played a large part in the response of the Boxers.

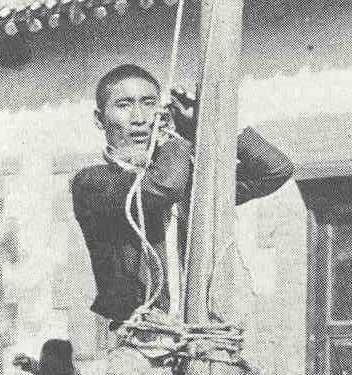

Chinese undergoing missionary punishment as a thief

(click on image for fuller photograph)

By the spring of 1900, the incidents had escalated in both number and violence, partly because of the demoralizing effects of the severe drought that had lasted for nearly a year. In the absence of any concrete group to blame, the Chinese peasants, poor and hungry, once again turned to the foreigners and Christian Chinese as the cause of their problems.

In May 1900, the Boxers began openly attacking Christians and foreigners in China. These actions resulted in the commission of an international relief force that arrived in the area that June. This small force, some 2,000 men, was turned back by the Boxers, and, soon thereafter, the dowager empress, citing a false report that foreign powers had demanded power be returned to the Emperor, declared that all foreigners be killed. This resulted in the siege of foreign legations and the indiscriminate murder of any westerner found in the city. Lasting nearly eight weeks, the Boxer's siege of Beijing finally ended on August 14 when an international force captured the city, forcing Tz'u-hsi and her court to flee to Siam. Reparations were made for the damages to foreign property and the loss of life after the Uprising and the dowager empress was forced to excuse her actions as having been misled by the conservatives and to promise that the courts would now support reforms.

[top]