by Jonathan Svarka, class of 2007

spring 2004

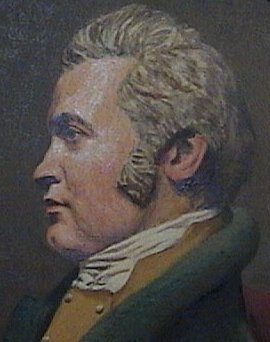

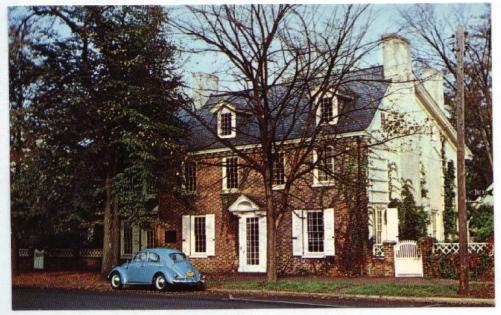

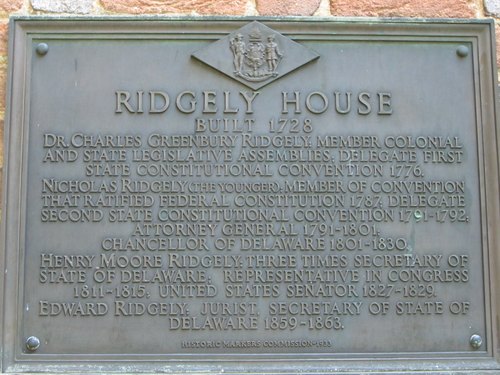

In 1832, a Delaware statesman retired to his home in Dover. After nearly 30 years of service to his state and his nation, he decided to leave public life to work the land. He still held his position as the president of the Farmers' Bank of Delaware, a position he had held since 1807, but had given up his previous public offices. The former United States Congressman and Senator returned to his House on Dover Green, the same house he had been born in, to live the quiet life of farming. He had survived a duel, arranged and preserved the Delaware archives, and reformed his home county of Kent during his fifty-three years. His name was Henry Moore Ridgely. He would approach his task of farming just as he had done before with all previous undertakings, with diligence and determination.

Henry Moore Ridgely was born in Dover, Delaware on August 6, 1779.1 His father, Charles, was a doctor who had lost his first wife. A deeply religious man, he found sympathy in Henry's mother, Ann Moore, whom he married in June 1774. Charles had four small sons from the previous marriage, and during the next twenty years Anne gave birth to five more children. Anne tried to bring both families together through her character and personality. Henry, along with the other children, was brought up in a strict household that valued education. His first glimpse of tragedy came in November 1785 when his father died from bout with a long illness. Ann, although grief-stricken, strived to take on the responsibilities of a single parent. She educated her husband's children, managed the property, and tried to make her house a home for all the children.2 Her influence can be seen in all her children, including Henry.

Henry received his education from his mother until 1794 when he began attending the New Ark Academy, in Newark, Delaware. He studied there until 1795, when the instructor, William Thompson, left for Dickinson College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. Henry and his brother George accompanied Thompson and began their higher education at Dickinson.3 Henry was a good student, but was scolded by his mother for his poor penmanship and frivolous spending habits.4 In February of his senior year at Dickinson, 1797, he wrote an essay that demonstrated his strong religious beliefs and steadfast disposition. He was a passionate writer who stood up for his views:

If the Skeptics were to really doubted of every kind of evidence but mathematical, we have reason to believe they would be put to some inconvenience, for if a Skeptic were to refuse to remove himself from his house which he knew was on fire or to extinguish the flame, until it could be demonstrated to him by the mathematics that it would destroy his property; the world wd [sic] be rid of him his house & philosophy together -.5

In the essay, the reader can see the beginning of the pleasant,

strong speaker he would become in his later years.

In the spring of 1797, Henry Moore Ridgely graduated from Dickinson

College. He chose to study law under Charles Smith of Lancaster. The reasoning

behind his staying in Pennsylvania was to be close to his love interest

Elizabeth Wilson of Carlisle.6 He later proposed

to her and they were engaged.7 During his time

at Lancaster, he became restless and found it monotonous.8

Like many men of the era, he wished for glory and honor in the military.

In 1798, a naval war with France brewed.9 He

wanted to join the military, but was influenced by his mother to stay with

his law studies. She told him that he did not have enough discipline to

make it and he was needed more in the civilian realm than in military affairs.

He reluctantly followed his mother's advice.10

As a result of his dislike of Lancaster and his spending habits, he was

brought home to be taught by his older brother Nicholas.11

He studied with his brother for four years and in 1802 was admitted to

the bar in Delaware. He started practicing in Dover and became a prominent

attorney.12

In May of that same year, his engagement was called off with Miss Wilson.

They could not agree on a wedding date. Henry wanted it during that year,

but she resisted.13 Elizabeth never loved him

and only accepted the proposal because of her mother.14

Dejected but not giving up he started courting a lovely childhood friend

of his sister during that summer. Her name was Sally Banning and he soon

fell in love with her. At fifteen, she was nine years younger than Henry.

They were engaged by September and were to be married the next year. Then,

in April 1803, tragedy struck Henry.

On April 20, 1803, Henry was involved in an engagement that nearly took his life. He was the messenger for Dr. Barratt of Dover. Dr. Barratt was insulted by William Shields of New Castle and sent Ridgely to give Shields the invitation for a duel. Ridgely arrived with the message, but Shields turned down the duel with Mr. Barratt. Enraged that he would bring such a message, Shields challenged Ridgely to a duel. Ridgely felt an obligation to the code of dueling and felt a threat to his honor. He accepted and the two men fought. After the smoke cleared, Ridgely was severely wounded in the arm.15 Weak and in pain, he was taken to Dr. William McKee of Wilmington to receive treatment.

McKee treated his wounds, but his step-daughter nursed him back to health. His step-daughter was Henry's fiancee Sally Banning.16 Henry corresponded with Sally after his recovery, only sixteen, but she was reluctant to marry. She thought herself too young to be married.17 Henry had been through the same grievances with Elizabeth and he was not going to be embarrassed again. Sally was soon given an ultimatum to set a marriage date or terminate the marriage.18 She accepted a fall wedding and although it had to be postponed a week due to Sally coming down with a case of gumboils, they were married on November 20, 1803.19 The newlyweds moved into the Ridgely House on Dover Green soon after. Henry Moore Ridgely resumed his practice and soon was elected to the public forum.

Henry and Sally had fifteen children, seven of which did not make it past infancy. The eldest Charles George was born in 1804. Elizabeth, Ann, Henry, Nicholas, George, Willamina Moore, and Edward soon followed. Sally found little time for relaxation and she was usually worn down from illness. The two had a happy marriage with warm intellectual companionship throughout. Sally was a talented gardener, loved pets, and was remembered by others for her kindness.25 She made sure the children had a happy home while Henry was away at Washington.

Henry Moore Ridgely began his retired life at Linden Farm just west of the House.26 He had turned down many offers for public offices during his retirement years continuing to hold his old position as president of Farmers'; Bank. In 1837, Sally passed away after suffering from tuberculosis. Henry called on his sister Ann to keep him company and take care of the children. Henry did not want to keep his sister from marriage so he proposed to his friend, Governor Cornelius Comegys' daughter, Sally. She was younger than Ridgely's eldest son and outlived him nearly forty years. They were married on May 17, 1842.27

She was a comfort to Henry during his last few years although his children never accepted her. Six years after their marriage, Henry suffered a paralytic stroke. He never regained full use of his body. On his sixty-eighth birthday, Henry Moore Ridgely passed away in Dover.28 Before he died, he told his wife what he wanted his epitaph to be: "Henry Moore Ridgely, first son of Charles and Ann Moore his second wife. Born on August 6th day 1779 year, Died on 6th of August 1847 in the blessed hope of immortality;"29 Henry Moore Ridgely's hope for immortality lives on.

End notes

1. Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Henry

Moore Ridgely. (http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/biodisplay.pl?index=R000245.)

2. Leon deValinger, Jr. ed. A Calendar of Ridgely Family Letters

1742-1899: Volume 1. (Milford: Milford Chronicle, 1948), 94-96.

3. Ibid., 131.

4. Ibid., 140-141.

5. Henry Moore Ridgely. Essay Against Scepticism. (February

1797).

6. Leon deValinger, Jr. ed. A Calendar of Ridgely Family Letters

1742-1899: Volume 2. (Milford: Milford Chronicle, 1948), 87.

7. Ibid., 102.

8. de Vallinger, Jr. A Calendar of Ridgely Family Letters 1742-1899:

Volume 1., 179.

9. Naval History Bibliography. Naval History: Federal/Quasi War. (http://www.history.navy.mil/biblio/biblio4/biblio4a.htm).

10. de Vallinger, Jr. A Calendar of Ridgely Family Letters 1742-1899:

Volume 1., 180.

11. Ibid., 182.

12. deValinger, Jr. ed. A Calendar of Ridgely Family Letters 1742-1899:

Volume 2., 87.

13. Mabel Lloyd Ridgely. What Them Befell: The Ridgelys of Delaware

& Their Circle in Colonial & Federal Times: Letters 1751-1890.

(Portland, Maine: American Press, 1949), 305.

14. Ibid., 305.

15. Thomas J. Scharf. History of Delaware: 1609-1888. (Philadelphia:

L.J. Richards, 1888), 572.

16. Mabel Lloyd Ridgely. Letters 1751-1890., 303-5.

17. de Vallinger, Jr. A Calendar of Ridgely Family Letters 1742-1899:

Volume 2., 104-5.

18. Ibid., 105.

19. Ibid., 106.

20. Scharf. History of Delaware., 572.

21. Ibid., 572.

22. de Vallinger, Jr. Volume 2., 87.

23. de Vallinger, Jr. Volume 2., 88.

24. Scharf. 572.

25. de Vallinger, Jr. Volume 2., 90.

26. Ibid., 20.

27. Ibid., 93.

28. Ibid., 21.

29. Leon deValinger, Jr. ed. A Calendar of Ridgely Family Letters

1742-1899: Volume 3. (Milford: Milford Chronicle, 1948), 99

Return to Encyclopedia Dickinsonia