| Thoughts of fighting and dying for the glory

of a noble cause have swelled many a heart throughout the ages, particularly

those of young men eager to prove themselves. The American Civil

War was no exception. The young men who filled the ranks of both

sides shared a common bond with their counterparts of wars past: an eagerness

to uphold their cause by engaging in destruction and bloodshed, the scope

of which their naive young minds could not comprehend. And for most,

as with wars past, once the initial euphoria wore off, the harsh reality

of army life and battle quickly transformed bright enthusiasm into despairing

weariness and despair as the war dragged on. A few were able

to relate in their letters home their feelings and to follow the correspondence

of such young men is to trace that transformation from youthful innocence

to the melancholy of experience.

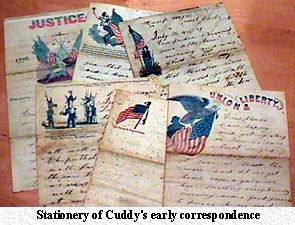

The Dickinson College Archives and Special Collections houses a collection of letters such as these. Comprised of eighty pieces of correspondence, this collection chronicles the military service of John Taylor Cuddy, a Carlisle, Pennsylvania boy who enlisted in the Pennsylvania Reserves after the outbreak of war in the spring of 1861. The majority of the letters Cuddy wrote to his family and friends at home in Carlisle during the term of his enlistment, from June 1861 to late April 1864. Taken together, they paint a portrait of a young man whose falls victim to this wartime mentality and learns its awful lessons. Little is known of Cuddy’s early life. He was born the second son of John H. and Agnes Cuddy of Carlisle on October 17, 1844. In addition to John Taylor, the Cuddys had four other sons, Alfred, Robert, Edward, and Frank, and a daughter, Margaret (Maggie); two other sons, William and James, had died in 1849.1 The family owned and operated a distillery in town; when he enlisted, John Taylor denoted his occupation as “distiller” and referred to the “distilling house” in his letters. Cuddy’s grammar and spelling are very similar to that of his mother, so he may have received his education at home.

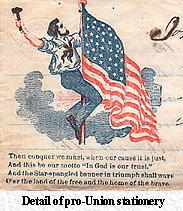

Cuddy’s first letters to his family leave no misconceptions as to why he enlisted. He is adamant in his defense of the Union and its principles, and expounds on this subject. Letters from Camp Wayne captured the patriotism and excitement of the young men who enlisted to preserve the Union. tell all my frendes that we listed for a good cause and that wase to save our contry and to kep the stares and stripes[,] and we hope that god will helpe us to keep the flag up fore ever[.] the cuntry is ours for ever and if we git in a battel and git killed we hope that god will save our soles fore ever[,] and i pray to him fore help and trust in him for ever....3Although Cuddy had not yet left training camp, he remained extremely confident in the might of the Union army and its ability to put down the Rebellion. i belive that the north is going to rase a big armey and then we will make the south in the unian agin[.] the south cannot stand before our army[.] we will soon lick the south and then we will come home and we will spend a happy life with you agin…. We have more fun here than ever you saw[.] we can git a pass wen never we want to go to town and we ware down at the brandy winie yestday at the battel ground ware the battel of brandy wine was faught….4Of course, Cuddy had probably never met or conversed with anyone from the South. His words, however, ring with the bravado of an eager young soldier. The first few months of Cuddy’s new army life were relatively uneventful. The 36th Regiment trained at Camp Wayne for six weeks before traveling via train to Washington, DC, where the 7th Reserve was mustered into service in the United States Army. They made camp at Great Falls, Maryland in late August; Cuddy had his first direct encounter with the Confederacy on 24 August when its artillery shelled his camp for two days. One soldier was wounded in the shelling, but no retaliation came, much to the chagrin of the reservists who were eager to engage the enemy. The regiment remained at Great Falls until October; they then marched to Langley, Virginia on the Potomac River to establish winter camp. Although they formed the extreme right flank of the Army of the Potomac, the regiment did not see any action all winter. They had been deployed for the Battle of Dranesville on 20 December but arrived too late to participate and so returned to camp.5

The regiment finally broke camp in mid-March

1862 and moved to Alexandria, Virginia. The spring rains created

a mess of mud and muck through which the army had to march, and the dismalness

certainly took its toll on morale.

we left our old camp last monday and have ben marching all week and are now one mile from Alexander[?] now[,] but we do not now how long we will stay for[.] we are going to some plase on water before long[.] we had one of the hardest weeks that ever i saw[;] we ware out all the time and it was wet all the time[.] we are all well[.] i send my love to you all and hope to see you all before long[.] we have manasses and i think this ware will soon be over and then i hope to git home again[.] we marched every day about seventeen miles last week[.] We are one mile from Alexander now but we now not wen we will leave this[.] it has been a wet week and we ware aut all the time[.] we have no tents now for we are marching every day[.] we are all well[.] i am happy to send my love to you all[.] i hope to get home in a few months now[.] we have ben nearly starved for the roads has ben so bad that we could not git our provisons after us[.] i would like if you would send me one doller in the next letter you rite to me....7This letter contains the first intimation of Cuddy’s frustration that the war is not yet over and that “soldgering” does not hold the excitement that it once did. He had been in the army for ten months and had not yet seen any real fighting; his only duties seemed to be marching through mud and going out on picket duty. His letter of 30 April 1862 indicates that the reality of the situation is beginning to set in for him and his fellow soldiers: “i think in a few monthes more this ware will be over for i am tiard of it[.] i have seen a nuf of vergineya now[.] i have ben soldgering a leven monthes now[.] i would like to be with you all tonite but i can not.”8 Spirits were lifted briefly when Captain Henderson, the man who helped form the Fencibles, visited and mentioned that he might be able to arrange for the regiment to return to Carlisle. Cuddy and his colleagues were much excited at the prospect; the drudgery of army life would be tolerable if they were at least closer to home. However, the transfer was never made, and the regiment remained in Virginia. For the next few months, they moved from camp to camp, finally settling on the Chickahominy River near Richmond. Here, as part of the 2nd Brigade, they were attached to General Fitz John Porter’s 5th Army Corps. On 26 June 1862, the regiment finally engaged

in its first real battle at Gaines’ Mill and Mechanicsville. Cuddy,

as part of Company A, was deployed as a skirmisher. On the next day

his company moved to the left side of the line as a reserve. The

Confederates took control of the field, however, and the Union army retreated

back across the Chickahominy to the Charles City Road, which it did not

reach until late in the evening of 29 June. Here they were again

attacked, the two sides engaging in fierce hand to hand combat with bayonets;

this time the rebels were repulsed, and the Union army moved to Harrison’s

Landing to regroup and rest. Casualties had been heavy in the 36th.

Only about 200 remained untouched in the regiment, 301 having been killed,

wounded, or gone missing; several officers, including Captain Henderson,

were among the wounded.9

Cuddy survived the battles physically unscathed, but not mentally or emotionally;

his desire to return home increased dramatically. Just a week later,

his letter of 8 July, though still with signs of bravado, paints a bleak

picture for his family back home.

Dear friends[,] with plesure i take the oppertunity to rite a few lines to you to let you know that i am alive yet[.] i hope that thes few lines may find you all well[.] we have harde times for the last week[.] we had three fights[:] one on thersday and fryday and on Monday[,] but i got throught safe[.] we had the hardest fighting that has ben done in this ware[.] we lost too generals out of our devison[?][.] they ware taken prisners ando our begade general was wounded very bad[.] we lost ninteen ore twenty men out of our company[.] this is three of our boys in richmond[.] John Natcher is in richmond a prisner[.] we took a prisner on Monday[,] he is one of them mastiers[?] that ust to work in the foundry[.] we have some harde times but we are giting along as well as ever[.] wate is left of us[,] we are in the rear of the hole army now[.] i do not think that we will git in eny more fites for a wile for our [reserve] core is cut up very bad[.] i have not much to rite now for i have no inke and my pensle is bad... i think i will git through this ware for i was in three of the hardest fights that can be[.] the balls came as thick as hale all around me but none of them hit me....10

Dear friends[,] this ware is an auffel thing[.] fighting for ngroes now is a bad thing but i hope that this ware will be over till spring[.] old abe done a bad thing wen he freed all the slaves[;] now the rebels is fighting for ther rites[.] dear friend i wish that this ware was over and i was at home with you all again[.] i think that i will not go a soldgerning eny more for i am tiard of ware now[.] i hope to get through this ware safe.... What have we gained by fighting yet we lost more then we ganed[.] i hope that our devision will git to the state for to recrute[,] for we have only two thousand and five hundred men in our devision now[,] and if we get to the state i do think that we will not go out eny more[.] dear friends i wish that this ware was over and i was at home to nite with you all....12

The 7th Reserve fought heroically in the Battle of Fredericksburg of 10-12 December 1862; although the battle was ultimately a defeat for the Union army, soldiers in the 7th captured several enemy officers, soldiers, and souvenirs. Their losses, however, were also great. After the battle, the regiment established winter camp at Belle Plain on the Potomac; any attempts to cross the river were thwarted more by the mud and swollen waters than by enemy attacks. Conditions in camp were atrocious, and by spring the ranks had been greatly reduced as a result of the fierce fighting experienced in the fall and by sickness brought on by the inclement weather. Morale equally suffered when the entire division was ordered to duty in the Department of Washington, the main objective being the defense of the capital. In this capacity, the division marched to Alexandria in February 1863 before returning to Upton’s Hill where they had camped the previous summer. During this time Cuddy wrote to his parents every week, sometimes within a few days of his last letter. Army life for him and his colleagues had grown tedious; as Cuddy described it, “soldgern is geting played out....”13 His rhetoric turned from that of optimism for a swift and successful conclusion of the war, to the anticipation of mustering out. His continued frustration with the slavery situation became more evident, as did his growing concern about his survival. i hope and pray to god to spare me through this ware and let me get home safe again[.] time is long[,] but happy will be the day wen this ware is over and all of us old soldgers is at home again[.] i would like to get home for a weeke or so but i will wait till spring[,] then i will try for a ferlow[.] i am in good helth and happy but i am gitting tiard of this ware[,] for it lasts longer than i thought it would[.] but i think i can stand it the rest of my time[,] but then i will never soldger eny more[.] we are not fighting for what we ware wen we started out[;] we are fighting for the niggers now[.] Time flys fast but one year is a long time in the army[,] but i hope to god that this ware may be seteled till spring for all the soldgers is tiard of fighting for niggers....14

Leutenit S V Ruby commanding our company told me this evening to write to you to write to govener curton for me a fourlough[,] that is the only way to get one eny ways soon[.] tell him that i have bean in the army two years and have not had a fourlough yet and you wish to see me[.] ther is fore in the company a hed a me[,] but if you write to the govener he will send an order to the comander of the redgiment and i will get one right away[.] write to him right a way as soon as you get this letter[,] for we may go to the frunt before long and then i would not get home for a nother year[.] tell him the company and redgiment that i belong to and tell him that i have not had a furlough yet[.] John A Natcher got his furlough tht way and it is the quickest way to get one[.] i send my love to you all and hope to get home soon to see you all[.] Leutenit Ruby told me he would get it as soon as the govener would send a recomendation to him and Curton will rite to him as soon as you write to him[.] write soon to him....15To further advance his cause, Cuddy even tried to evoke sympathy and guilt from his father by stating that he could wait another year to come home if they didn’t want to see him, but that he really wanted to see all of them.16 John H. Cuddy did write to Governor Curtin on behalf of his son and was granted the furlough; the reply from Curtin’s secretary dated 10 June 1863 is included in this manuscript collection. Unfortunately for the younger Cuddy, he would never be able to take advantage of the governor’s favor: Confederate forces invaded Pennsylvania just days after the furlough was granted. Cuddy apparently never learned of the furlough, as he did not mention it. He did, however, express the frustrations the members of the regiment t felt when they were not able to defend their homes themselves. we herd that the rebels is in pennsylvanay now[.] we wish we ware up ther[;] we would put them out of it in a hurry[,] i am sure of it[.] we expect to be ordered up ther in a few days[.] i hope we may for i would like to fight the rebels in pennsylvana for i think we could git them[.] I hope that they may get them out of the state[,] for i dont like to see the rebeles up ther and us down here[.] i hope we may get to harrisburg and then we can get home to see you all[.] i send my love to you all and hope to get home before long....17The regiment was still stationed in Washington; they were not deployed during the Gettysburg campaign and therefore did not participate in one of the most important battles of the war, and one that particularly brought the war home to their families. After the battle, a family friend wrote to Cuddy’s mother Agnes, inquiring about the occupation of Carlisle, particularly the burning of the garrison there. She also asked for an update on Cuddy’s situation, as she confessed to Agnes that she had a dream that he had been wounded.18 Of course, the only wound Cuddy received was to his pride, as he was not able to defend his home against the rebel invaders. Cuddy’s life in the army was again relatively uneventful for the next nine months, as the regiment remained in Washington until April 1864. Provost and guard duty occupied most of the soldiers’ time. During this period Cuddy’s letters return to the discussion of mundane tasks and his overwhelming desire to return home. Each letter contains a report of the days remaining in his term of service; he expected to be mustered out with the rest of the regiment in mid-May, and to be home within a few months. His letter of 11 April 1864 reflects his happiness at the prospect of being able to arrive home safe and to spend the rest of his life with his loving family. However, this letter is the final one written by Cuddy in the collection.   While at Andersonville I did not suppose the rebels had a worse prison in the South, but I have now found out that they have. This den is ten times worse than that at Andersonville. Our rations are smaller and of poorer quality, wood more scarce, lice plentier, shelters worn out, and cold weather coming on....21Cuddy had survived the horrendous conditions at Andersonville, but with his health undoubtedly ruined, he could not last in the squalor at Florence. John Faller, a sergeant of Company A who had lost his brother Leo at Antietam, wrote that Cuddy, broken by the mental and physical tortures of imprisonment, died on September 29, 1864, nearly five months after his capture, four months after he was to come home, and eighteen days before his twentieth birthday.22 Sherman’s “March to the Sea” in November and December 1864 secured the release of the Florence prisoners within a few months, but many of the regiment had already succumbed to the exposure suffered at the prisons. Many more would die within a few short years of returning home, never having fully recovered. The remaining 110 members of the regiment had continued to fight under Captain Samuel King, although ultimately the Wilderness Campaign was not a success for the Union army. The ranks having been completely decimated by the battle, those who remained were mustered out of the army on 16 June 1864. Both Samuel Elliot and John Faller survived the horrors of Florence and returned to Carlisle in 1865. The importance of the John Taylor Cuddy collection lies in its depiction of the evolution of a young soldier from brash youth to weary veteran. Through his own words, Cuddy becomes more than another faceless casualty of the Civil War; the reader is privy to his thoughts on the Union and on slavery, and to his changing opinion of the war effort as the fighting continues year after year. While Cuddy’s service did not have a great impact on the war itself, nor do his letters reveal any novel details of military engagements, they illustrate the human face of the war. They remind the reader that, as with most wars, these were real men fighting an enemy, exactly like themselves, for reasons that they did not entirely comprehend. Although Cuddy ultimately gave his life for his country, the record of that life is not lost, and his letters reveal that he was just an average young man with as much enthusiasm, excitement, disenchantment, and fear as any other human being. Perhaps the best illustration of that human face comes from the most poignant document in the collection. It is not one of Cuddy’s homesick notes to his family, or the letter granting his furlough, but is instead the only letter written to Cuddy. Agnes Cuddy wrote to her son on 1 May 1864, expressing her dismay that he was being sent to the front again as well as her hopes that they would be reunited soon after so long a time. Unfortunately for the Cuddys, that reunion would never come. hoping that these few lines may find you well to inform you we receved a letter from you last week and we all whare very glad to hear from you that you whare well[.] we whare very sorry to hear that you had to go in frunt a gain[,] but we hope and trust to god that you may bee saved throw this war[.] you have not long to stay in the army now and i hope you will get throw safe and get home a gain[,] for it has been a long time dear son since you whare at home[,] but we hope it may not be very long till you get home now[.] i wish you had your discharge now that you could come now[,] for we would be very glad to see you[.] i hope you will not be sent in to eny more battles for you have done your duty like a good boy....23John Taylor Cuddy never received this last letter from his mother; her loving sentiments were never able to comfort her son at the end of his life when he needed them the most. 1. Sarah Woods Parkinson, Memories of Carlisle’s Old Graveyard (Carlisle, PA: Mary Kirtley Lamberton, 1930), 53. 2. Milton Flower, ed., Dear Folks at Home: the Civil War Letters of Leo W. and John I. Faller, with an Account of Andersonville (Carlisle, PA: Cumberland County Historical Society, 1963), 2. 3. John Taylor Cuddy, Letter to John H. Cuddy, 30 June 1861. John T. Cuddy Papers (MC 2001.9); Dickinson College Archives and Special Collections. 4. Ibid., Letter to John H. Cuddy, 7 July 1861. John T. Cuddy Papers (MC 2001.9); Dickinson College Archives and Special Collections. 5. Samuel P. Bates, History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5, vol 1. (Harrisburg: B. Singerly, 1869), 722. 6. John Taylor Cuddy, Letter to John H. Cuddy, 6 January 1862. John T. Cuddy Papers (MC 2001.9); Dickinson College Archives and Special Collections. 7. Ibid., Letter to John H. Cuddy, 17 March 1862. John T. Cuddy Papers (MC 2001.9); Dickinson College Archives and Special Collections. 8. Ibid., Letter to John H. Cuddy, 30 April 1862. John T. Cuddy Papers (MC 2001.9); Dickinson College Archives and Special Collections. 10. John Taylor Cuddy, Letter to John H. Cuddy, 8 July 1862. John T. Cuddy Papers (MC 2001.9); Dickinson College Archives and Special Collections. 12. John Taylor Cuddy, Letter to John H. Cuddy, 16 January 1863. John T. Cuddy Papers (MC 2001.9); Dickinson College Archives and Special Collections. 13. Ibid., Letter to John H. Cuddy, 3 March 1863. John T. Cuddy Papers (MC 2001.9); Dickinson College Archives and Special Collections. 15. Ibid., Letter to John H. Cuddy, 21 May 1863. John T. Cuddy Papers (MC 2001.9); Dickinson College Archives and Special Collections. 16. Ibid., Letter to John H. Cuddy, 28 May 1863. John T. Cuddy Papers (MC 2001.9); Dickinson College Archives and Special Collections. 17. Ibid., Letter to John H. Cuddy, 15 June 1863. John T. Cuddy Papers (MC 2001.9); Dickinson College Archives and Special Collections. 18. Susanna Thompson, Letter to Agnes Cuddy, July 17, 1863. John T. Cuddy Papers (MC 2001.9); Dickinson College Archives and Special Collections. 21. Diary of Samuel Elliot, reprinted in Bates, 732. 23. Agnes Cuddy, Letter to John Taylor Cuddy, 1 May 1864. John T. Cuddy Papers (MC 2001.9); Dickinson College Archives and Special Collections. |

After

the attack upon Fort Sumter in April 1861, President Abraham Lincoln sent

out a call for 75,000 volunteers to serve for a term of three months.

Throughout the Union, men enlisted by the thousands; within a week of this

request, four volunteer companies of fifty to one hundred men were organized

in Carlisle. One of the companies, led by Captain Robert M. Henderson,

was known as the “Carlisle Fencibles”; although these men enlisted for

a three-year term instead of three months, they fully expected the war

to be over within months.

After

the attack upon Fort Sumter in April 1861, President Abraham Lincoln sent

out a call for 75,000 volunteers to serve for a term of three months.

Throughout the Union, men enlisted by the thousands; within a week of this

request, four volunteer companies of fifty to one hundred men were organized

in Carlisle. One of the companies, led by Captain Robert M. Henderson,

was known as the “Carlisle Fencibles”; although these men enlisted for

a three-year term instead of three months, they fully expected the war

to be over within months. Cuddy

wrote home many times during his stay at the winter camp, but as nothing

very exciting was happening, these letters discuss such mundane topics

as being paid and descriptions of the countryside. He still expected

the war to be resolved quickly and held the rebels in low esteem: “we

are expecting a fite every day but the rebels will not atacket us for they

are afrade of us[.] we have good times at soldgering[.] the rebels is very

strong up at leas burg.”

Cuddy

wrote home many times during his stay at the winter camp, but as nothing

very exciting was happening, these letters discuss such mundane topics

as being paid and descriptions of the countryside. He still expected

the war to be resolved quickly and held the rebels in low esteem: “we

are expecting a fite every day but the rebels will not atacket us for they

are afrade of us[.] we have good times at soldgering[.] the rebels is very

strong up at leas burg.” Still,

this post-Antietam letter is interesting also in that Cuddy comments on

a very important development in the political aspect of the war.

Immediately following the Battle of Antietam, President Lincoln issued

a preliminary decree that served as a precursor to the Emancipation Proclamation.

Although this decree was intended to demoralize southerners by inciting

the slaves in Confederate territories to fight for the Union, it also adversely

effected the northerners who had thus far achieved little success in their

fight to preserve the Union. In their minds, by making this decree

Lincoln had altered the cause of the war from the preservation of the Union

to the emancipation of the slaves. While the former was the rallying

cry of most northern soldiers, the latter was anything but; northerners

were opposed to slavery, but they did not want to fight for blacks.

Lincoln had shifted the focus of the war, which angered the common soldier

and added to his disillusionment. Cuddy was no exception, and he

voiced his clear disapproval.

Still,

this post-Antietam letter is interesting also in that Cuddy comments on

a very important development in the political aspect of the war.

Immediately following the Battle of Antietam, President Lincoln issued

a preliminary decree that served as a precursor to the Emancipation Proclamation.

Although this decree was intended to demoralize southerners by inciting

the slaves in Confederate territories to fight for the Union, it also adversely

effected the northerners who had thus far achieved little success in their

fight to preserve the Union. In their minds, by making this decree

Lincoln had altered the cause of the war from the preservation of the Union

to the emancipation of the slaves. While the former was the rallying

cry of most northern soldiers, the latter was anything but; northerners

were opposed to slavery, but they did not want to fight for blacks.

Lincoln had shifted the focus of the war, which angered the common soldier

and added to his disillusionment. Cuddy was no exception, and he

voiced his clear disapproval.

Life

did not improve for the soldiers, as their orders kept them in the general

vicinity of Washington and Alexandria. They returned to camp at Washington

in May but saw no military action. Frustrated, Cuddy decided to ask

for a furlough. He wrote home five times in the month of May, asking

his father to write to Pennsylvania Governor Andrew Curtin to request a

furlough. Curtin had developed a reputation for being an ally of

Pennsylvania soldiers, and Cuddy felt certain that this was the only means

of securing a pass. In his letters to his father, he justified his

desire to come home, stating that he had been in the army for nearly two

years and had always done his duty as a good soldier and citizen.

Life

did not improve for the soldiers, as their orders kept them in the general

vicinity of Washington and Alexandria. They returned to camp at Washington

in May but saw no military action. Frustrated, Cuddy decided to ask

for a furlough. He wrote home five times in the month of May, asking

his father to write to Pennsylvania Governor Andrew Curtin to request a

furlough. Curtin had developed a reputation for being an ally of

Pennsylvania soldiers, and Cuddy felt certain that this was the only means

of securing a pass. In his letters to his father, he justified his

desire to come home, stating that he had been in the army for nearly two

years and had always done his duty as a good soldier and citizen.