© 2000 Dickinson College. All rights reserved

|

Number

13

© 2000 Dickinson College. All rights reserved |

| Horatio Collins King, Class of 1858, was one of Dickinson College's most talented and esteemed graduates. An accomplished lawyer and a patriotic Civil War veteran, he is perhaps best remembered today as the author of the words to the college Alma Mater. Yet he was also the only known Dickinsonian to have regularly kept a journal for all four of his college years. This remarkable document, housed in the Dickinson College Library's Department of Special Collections, spans the period from September 1854 to August 1858 and totals 596 pages with an extensive index and a variety of newspaper clippings and mementoes collected by its author. The existence of the index and the fact that two obituaries from 1860 and 1861 are pasted into its pages, suggest that the journal was completed years after King graduated. That approximately one hundred pages have been removed with a razor blade shows a more rigorous form of editing; whether this was done by King or a surviving relative is unknown.(1) Despite the omissions, however, the diary provides an intimate glimpse into the thoughts and feelings of a young man who entered Dickinson as a freshman at the age of sixteen, rebellious and immature academically and in his relationships with women. The journal chronicles everything from King's romantic desires, to his sophomoric pranks, to his impatience with boring lectures, dry sermons, tedious recitations, and inept professors, revealing an emotional character with much to teach us about undergraduate life in the mid-nineteenth-century United States. |

|

Horatio Collins King was born on December 22, 1837, in Portland, Maine, the eldest son of Horatio and Anne (Collins) King, who were married on May 25, 1835. King moved with his parents to Washington, D.C., when he was eighteen months old, because his father received a position in the Post Office Department. By 1854, the elder King (June 21, 1811 - May 20, 1897) had risen to the post of First Assistant Postmaster General. In the closing months of the Buchanan administration in 1861, he briefly joined the cabinet as Postmaster General. Young Horatio meantime attended Rittenhouse Academy and later preparatory school at Emory and Henry College in Virginia. He earned a Bachelor of Arts degree at Dickinson in 1858 and a Master of Arts from the same institution in 1863. In these later educational efforts, the younger King followed the movements of his uncle, the Rev. Dr. Charles Collins, who left the presidency of Emory and Henry to take up the same post at Dickinson in 1852. In October 1862, King married Emma Carter Stebbins, daughter of a successful merchant in New York City. She died in March 1864, followed by their only child, Mabel, who lived from February to June 1864. In June 1866, the widowed King married Esther Augusta Howard (1845-1925). The couple had nine children, six of whom lived past their first year.(2) |

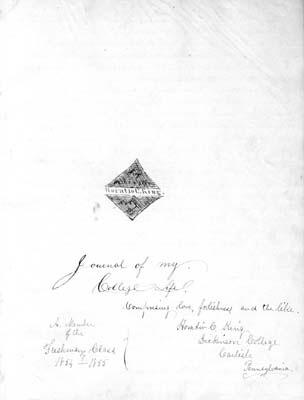

| Title page of Horatio

Collins King's journal.

King Collection, Box 2, Folder 16, Department of Special Collections, Dickinson College Library. |

| After receiving his Dickinson bachelor's degree, King studied law for two years with Edwin McMasters Stanton in Washington, D.C. Stanton–a great influence on King's later career–was appointed Attorney-General by President James Buchanan on December 20, 1860, because of his success in patent, land claims, and criminal cases. King was admitted to the New York State Bar in May 1861, and commenced working in the New York City office of Edgar S. Van Winkle, Esq. After the outbreak of the Civil War, King rekindled his ties with Stanton, who became President Lincoln's Secretary of War in January 1862. In August of that year, Secretary Stanton gave King an appointment as Captain-Quartermaster under Major-General Silas Casey, and later assigned him to Department Headquarters under Generals Samuel Peter Heintzelman and Christopher Columbus Augur. Next, King served as Chief Quartermaster of Gustavus Adolphus De Russy's battalion which fought from the Potomac River to Alexandria, Virginia. King wanted to see more "arduous and dangerous service," so he petitioned Stanton to reassign him. The Secretary obliged by posting him in February 1865 under Generals Phillip Henry Sheridan and Wesley Merritt in the Army of the Shenandoah. Rising within a few months to Chief Quartermaster and to Colonel of Volunteers on May 19, 1865, King fought with distinction in the Battle of Five Forks and later received the Congressional Medal of Honor for "most distinguished gallantry in action at or near Dinwiddie Court House, Virginia, March 31, 1865." King was honorably discharged in October 1865.(3) |

Horatio Collins King and his

sister,

|

| For over fifty years, King was a member

of the Plymouth Church in Brooklyn, New York, which was founded by his

father-in-law, John Tasker Howard. Henry Ward Beecher was pastor there

from 1847 until his death in 1887. The two men became as close as brothers.

King first became entranced by Beecher while at Dickinson. Along with eighteen

other students, he attended an abolitionist speech by Beecher at the First

Presbyterian Church in Harrisburg. According to King, all of the students

were Democrats and anti-abolitionists. Yet Beecher captivated his audience

for two hours with a speech entitled, "Equal Rights."(4)

On Tuesday, March 24, 1857, King wrote in his journal, "I listened to the

finest lecture it was ever my good fortune to hear. Notwithstanding I could

not accord with him in his fanatical views of 'Equal Rights' and Pulpit

Politics, still all must acknowledge it to be a masterly effusion from

the pen of a smart tho' misguided man."(5)

The Civil War and Beecher helped to change King's outlook, however. "The

three years which I devoted to the great war reversed my attitude towards

the slavery question," he later recalled, "and no one was happier than

myself when the escutcheon of slavery was wiped off our national emblem."(6)

In the fall of 1866, King began a legal affiliation with William G. Lathrop, Jr. and S.B. Brownell. He stayed with the firm until 1871 when he accepted a position as associate editor of the New York Star. He next took an assistant publisher position at the Christian Union in 1873 with Beecher as editor. In 1876, he became publisher of the Christian at Work which was edited by the Rev. Dr. Thomas De Witt Talmage. King left publishing and resumed his military career in March 1878. He joined the National Guard of New York where he was appointed major of the Thirteenth Regiment and, in 1879, judge advocate of the Fourth Brigade. Under New York governors Grover Cleveland and David Bennett Hill, King was named judge advocate general of the New York State Guard. In 1883, he became involved in politics when Mayor Seth Low made him a member of the Brooklyn Board of Education, a post he retained until 1894. After working on Grover Cleveland's presidential campaign in 1884, he continued his political involvement as delegate to Democratic national conventions. He also ran unsuccessfully as the Democratic candidate for secretary of state of New York in 1905. Later in his life, King spoke on behalf of both the Democratic and Republican parties, and became known as a Progressive Republican from 1900. He campaigned for the position of state controller in 1912 on the Progressive ticket. Active in a number of institutions, King served as secretary of the Army of the Potomac from 1877 until his death and as president of the organization in 1904. He was a trustee of Dickinson College from 1896 until 1918 and received a Doctorate of Laws degree from Allegheny College in 1897.(7) King spoke widely and often through lectures, post-prandial speeches, and dedications. His presentations often had Civil War topics: "General [William Tecumseh] Sherman," "Closing Days of the [Civil] War," and "Abraham Lincoln" are examples. King also spoke about friends such as Henry Ward Beecher and sometimes in support of politicians such as Theodore Roosevelt. Meantime, King was an avid music lover. He served as director of the Philharmonic Society of Brooklyn and was Chairman of its Music Committee. For a dozen years, he was assistant organist of Plymouth Church. King composed patriotic tunes such as All Hail Our Starry Banner! as well as a number of songs about Dickinson, includingthe Alma Mater Noble Dickinsonia and Dickinson For Aye! His poems similarly tend to concentrate on the college, the Civil War and military themes, and inspirational messages for children and young people. Among his books, reflecting kindred interests, are a History of Dickinson College and An Account of the Visit of the Thirteenth Regiment, N.G.,S.N.Y., to Montreal Canada.(8) King died of natural causes on November

15, 1918 at his home in Brooklyn, New York. In an interview a year earlier,

he vehemently emphasized his belief in the afterlife for those who served

well their God, their family, and their friends. At the funeral in King's

beloved Plymouth Church, the eulogy was provided by Beecher's successor,

Dr. Newell Dwight Hillis. The minister praised King's musical abilities

and his commitment to family and to church. According to Hillis, King missed

very few services at Plymouth and was a faithful friend, especially to

Beecher. Successful at almost anything that he did, he was a great patriot,

lawyer, writer, leader, and organizer. "With that superb enthusiasm for

the Republic General King lived and here in this old church, in the faith

of God, General King died," Hillis concluded. "In the spirit of sorrow

we recall him but in reality we are not sad. We are here to celebrate him.

We celebrate the quality of his manhood produced in this old church. We

are here to celebrate his capacity for friendship and his genius for service.

For him and for us there is no death."(9)

Sixty-four years earlier, in 1854, King had arrived at Dickinson College. He began to write his journal at a particularly important stage in the institution's history, as an ambitious financial plan attracted its largest entering class to date. In conjunction with Professor Herman Merrills Johnson, the college's new president, King's uncle Charles Collins, began a scholarship system that year, and made plans to boost enrollment while raising the college endowment to over $100,000. At the same time, trustees and faculty hoped to solicit students who could not easily afford higher education. Parents were encouraged to pay for their children's full course in advance, so that both families and the college benefitted. Four years of tuition was available for $25, ten years for $50, and twenty-five years for $100. These modest fees attracted parents in both the North and the South. King claims that there were over two hundred and fifty students at the college in his freshman year; the entering class was so large that some students were forced to seek lodging in private boarding houses in town. Writing in The Dickinsonian in 1873, King recalled that his "Freshman class, regular and irregular, numbered, if I remember rightly, about one-hundred and eight, and they came from nearly all parts of the land, even as far South as Georgia." (The "irregular" students that King cites probably did not attend preparatory school before coming to Dickinson.) About half the class left by sophomore year, because many students were not prepared for higher education. Only thirty-six students were graduated from the Class of 1858, yet this class was the largest in Dickinson's first one hundred and twenty-five years.(10) |

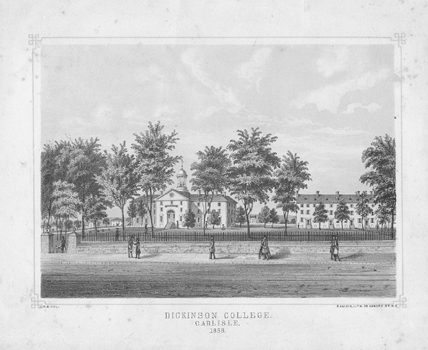

The Dickinson College campus

as it appeared in King's day.

|

The routine of students was quite regimented. The typical day included morning prayers at 6:30 a.m., breakfast at 7:30, evening recitations at 3:30, and evening prayers at 4:30. Dinner directly followed prayers and study hours began at 7:00 p.m. On Sundays, students often attended chapel two or three times as well as Sabbath School. They took oral and written exams. Recitations were oral summaries of the day's reading given by students in front of the class and the professor. These exercises were for the purpose of "cultivating the powers of memory, thought, and speech." Students also frequently needed to provide a "written analysis" of the text. Additionally, they were required to make Junior Orations, and were given four weeks to write and practice their commencement addresses.(11) As college historian Charles Coleman Sellers observes, "rigid discipline supporting a rigid and outmoded curriculum was creating a student world more and more apart from the faculty's." Not surprisingly, King's journal hardly ever praises his professors. The only mention of the faculty is when he complains about their "borous" lectures or when a good practical joke is played on them. King and his classmates especially hated "class recitations and between-class restrictions." These attitudes were reinforced by the fact that King suffered from stage fright and was, on the whole, sometimes unconfident of his academic abilities. He wrote in February 1873, "metaphysics was a bore, mathematics my abhorrence, and theology not my strongest point."(12) |

| Nonetheless, King was deeply influenced

at the college by his friends, his professors, the campus, and the town

of Carlisle. Among those influences was his uncle. To King, Collins was

both a demanding professor and a loving relative; his journal usually refers

to the college president as "Dr.," but occasionally uses "Uncle." King

was quite close with the family of Collins. In his journal, he frequently

makes note of "Mrs. Collins," and Dr. Collins' daughters, "Cis" and Mary.

He also took tea, ate dinner, and played music at the Collins home. Compared

with his predecessor, Jesse T. Peck, Collins was a very effective disciplinarian.

Peck was incensed when students played practical jokes on him or drowned

out his chapel speeches with foot stomping. Collins, on the other hand,

was not nearly so bothered by mischievous students. The president would

not speak until all students were quiet and sometimes forced them to remain

at evening services for hours. Collins, King said, was "firm," but rational

in his punishments. He entered into good relationships with students, once

they learned that he would not be pushed beyond his limits. "Although much

above the average instructor, his strongest characteristics were sound,

common sense, tact in the management of men and thorough efficiency in

business affairs," King wrote in The Dickinsonian in 1875. The president

"was always patient and level headed. He never said one thing and meant

another, and the boys soon learned to appreciate these qualities and respect

them."(13)

Still, in the day of Collins and King, students and professors did not often socialize or engage in intellectual activities together outside of recitations and lectures. To help fill the intellectual and social gap, King founded the "Shaksperean Club" during his freshman year with the "purpose of improvement in reading" and "oratory." The group met every Saturday, and each member wore a rectangular "Shaksperean Collar." Other students and faculty scoffed at their strange attire.(14) King and his friends were involved with dramatic organizations that performed Romeo and Juliet, Macbeth, and Hamlet. He once even read the part of Juliet because of his immature physical attributes. King also was a member of numerous bands. During his junior year, he led a "Calathumpian band" which traveled to churches, schools, professors' homes and street corners to sing mock serenades accompanied by "tin-pans, horns, flutes," and other instruments. Occasionally, King's musical groups would travel to other towns to hold formal performances for which they collected admissions fees.(15) His friends and he also enjoyed playing cards, euchre and dominoes. For sport, they engaged in rough and tumble, football, and handball. King also loved to eat. He frequented Carlisle's lager saloons, such as Schweitzer's, where he consumed beer, fried oysters, ice cream, and pretzels. In honor of such excursions, he and his friends called themselves "Schweitzer Guards."(16) Because the student body was all-male, college men were forced to seek female companionship in the town of Carlisle. King's journal goes into great detail concerning his personal life and love affairs. He met a young woman named Mattie Porter soon after he started his first semester at Dickinson and rapidly fell in love with her. Mattie is a major topic in the journal's discussions of King's personal life through his junior year. On October 10, 1854, he wrote, "I do think that Mattie is about the nicest piece of human nature I ever saw. She looked beautiful this evening." Two weeks later, he noted, "We sat together and talked all the evening. It seemed almost a heaven to me. Ah! she is an excellent, beautiful and good hearted girl." King spent many days and nights inside the Porter home, serenading Mattie and her sisters, Fannie, Sallie, Ida, and Mollie. He often brought flowers to their High Street abode and talked for hours. The young lovers exchanged rings, and King gave her his Union Philosophical Society badge. Sometimes, when Mattie and he kissed, they whispered Latin blessings or wishes in the ear of the other. They occasionally had quarrels, but always seemed to continue their friendship, even after the romance faded. During his junior and senior years, King had a serious love affair with Ellen Humes, with whom he primarily communicated by letter, as she lived outside of Carlisle. He even claimed that they were engaged to be married. King wrote on April 10, 1857, "Rec'd yesterday a degaure [daguerreotype] of my Ellen, of which I will not attempt a description, beautiful complexion–fine form–charming face–intellectual forehead." Meantime, he also flirted with Mallie Van Hoff, "Kate S.," Rachael Medary, Ellen Fleming, and "Miss Coyle."(17) The Class of 1858 loved to perform pranks on faculty, as did others before them. Moncure Conway, Class of 1849, famously had President Jesse T. Peck committed to a mental asylum in Staunton, Virginia, on March 7, 1849. Conway did this because a friend of his was punished for drinking and card playing. The students of the 1850s did not do anything so elaborate, but repeatedly engaged in small and large acts of mischief to get out of class work and lectures. During their junior year, King and his friends stole a textbook from Professor Johnson from which they did not enjoy reciting. The hated book, Mahan's Intellectual Philosophy, was an "abominable bore." The students performed an elaborate ceremony to bury the tome to be sure that no recitations could be requested from it for some time. "Farewell old Mahan: may you lie forever in that chilly grave, undisturbed, unchanged," King concludes in his journal. The new Carlisle coroner had the shallow grave on the corner of campus dug up because he feared infanticide.(18) Students enjoyed breaking into the private rooms of professors, as well. During their senior year, King and his friends attempted to steal a final examination in natural science from Professor William Carlisle Wilson's study. King also stole tallow from the pantry of Dr. Collins and used it on the blackboards of Professor Otis Henry Tiffany's classroom. The boards were unusable for twelve hours. On other occasions, fish oil and tar served the same purpose. Classroom stoves were a favorite target, too. Students poured water in them, took them apart, or stuffed them with odiferous asafetida and red pepper. Students stole furniture from East College and strung it in the trees. Additionally, the college bell was frequently tampered with because it was used by the faculty to signal prayers, recitations, and study hours. These practical jokes were easily done because professors and students often lived side by side, and bedrooms and classrooms were in the same buildings.(19) The faculty kept even closer watch over the students because of these actions. Students were required to attend all college activities, including prayers, recitations, and meals. They were not allowed to engage in any recreation without a faculty member. Sports were outlawed because they often caused fights among students, and playing cards were strictly forbidden, at least in theory. Students also were forced to be in their own rooms in the evening during study hours, as faculty often visited them. Of course, they could not bring women to their rooms at any time. Failure to comply with these rules resulted in minus marks; participating in dramatic productions, for instance, earned ten. Students were allowed only one hundred marks before being expelled, and public drunkenness could mean dismissal. Few students took the discipline system seriously, however. King and his classmates felt that the rules were too strict and were too often unfairly applied–and, as the journal clearly shows, they ignored them religiously. On June 13, 1856, King wrote in his journal, "Dr. Collins gave us a long lecture concerning our non-attendance to the rule which says, that students shall be in their rooms during study hours. The lecture made no impression on me, for I intend to go out just when I feel like it, and oftener if I choose." Cat-and-mouse games with the faculty were the inevitable result. King describes, for example, one professor who perched atop South College with a telescope in order to catch him dealing cards with friends across campus in West College. A more serious battle between faculty and students occurred when William I. Natcher (Class of 1858) died in Carlisle. The Class asked the faculty to suspend recitations in order for them to grieve their loss. The faculty resisted the request, so the students refused to attend recitations until after Natcher's burial. The next day, the faculty gave in, and all exercises were suspended. With only two hundred students, the college–even in its flush new times–would soon cease to exist if a significant number of them carried out their threat and went home.(20) Despite this oppressive environment, there were outlets for students' intellectual and social energies. The literary societies–Union Philosophical and Belles Lettres–and the Phi Kappa Sigma fraternity were particularly important. King was a member of both the Union Philosophical Society and Phi Kappa Sigma. Members of U.P.S. were elected and were required to pay fees to support its library. King wrote in The Dickinsonian in November 1882, "The two Literary Societies flourished vigorously and the halls were crowded every meeting and there was a healthy competition for the offices and especially for a place on the Anniversary programme."(21) The "Anniversary programme" was a ceremony of speeches conducted by the two societies the week before commencement. Both societies had gold badges and put great weight on the secrecy of all proceedings in order to spite the faculty. King also was pleased to learn that James Buchanan had been a member of U.P.S. and, in 1803, had read to that body an essay entitled "Danger of a too frequent connection with the Fair Sex." Many students, faculty, and alumni were enthralled when Buchanan was elected President of the United States on November 9, 1856.(22) Phi Kappa Sigma, which King joined in June 1856, was an illegal secret fraternity begun in 1854. With seventeen members, Phi Kappa Sigma was the only fraternity at Dickinson until 1859; the college's chapter was affiliated with the parent chapter at the University of Pennsylvania. By November 1857, the Dickinson faculty ordered the organization to disband, which only required its members to be even more secretive about their meetings. Fraternity members often had banquets, speeches, and other gatherings off-campus. On June 27, 1856, King wrote in his journal, "At 10 a.m. Phi Kappa Sigma society met in Belle Lttre Library and I received the 2d degree, by being informed of the signs of recognition, grip &c., &c., all of which I fear to entrust to paper, as their disclosure would cause great trouble. I am now a full member. Was shown the Archives, the skull and bones &c., &c."(23) A Dickinson education in the 1850s placed great stress on refining the oratorical abilities of students. This emphasis was part of a wider push for oral prowess in American culture. Lawrence W. Levine, in Highbrow/Lowbrow: The Emergence of Cultural Hierarchy in America, argues that, "although nineteenth-century Americans stressed the importance of literacy and built an impressive system of public education, theirs remained an oral world in which the spoken word was central."(24) Classroom lectures, then, were accompanied by a requirement that students make speeches as part of their mastery of the term's lessons. King, for example, was asked by his Latin and French grammar professor, Alexander Jacob Schem, to translate Carmen Saeculare in a "scanning style." Oratorical training also included the delivery of famous speeches from the past; King, for example, recreated in chapel a John Hancock oration on the Boston Massacre. Emphasis was placed on speech-writing as well as delivery. The sophomore class had its own exhibition in which it elected eight students to make original orations; King's was entitled, "The Glory and Shame of Spain." The Union Philosophical Society also had a separate exhibition, at which six students spoke. Students often attended the public lectures of professors as well. Dr. Collins gave a lecture during the second session called the "Democratic Tendencies of Science." King and Mattie attended two lectures that Professor Johnson delivered before the Union Fire Company, one on "woman's rights" and the other on "Hiawatha." King liked to critique the orations. He said of "woman's rights," "The lecture [was] quire [sic] prettily written and some of it quite witty." By contrast, he found Professor Wilson a "Borous man and lecturer." (25) Perhaps the most interesting element of King's journal is his personal development over the course of four years. King was confused and emotionally immature during his freshman and sophomore years. He was afraid to fall in love with Mattie. By his senior year, however, King was much more adept at courtship. He matured in other ways as well. As much as King complained about the faculty's boring lectures and the numerous recitations that each student was forced to give, he greatly appreciated his experiences at Dickinson. King was sometimes the leader and very often the follower of the students' vengeful pranks, but he seemed to grow out of them. As a junior and senior, he became annoyed by the mischievous doings of underclassmen. King began to see the difference between harmless pranks that stirred up professors and malicious damage that threatened the daily functioning of the college. He wrote in the second session of his junior year, "The Bell clapper was stolen and hid, several lecture room stoves destroyed and a variety of damage done generally. This wilful damaging of property is devoid of keenness and shows a bad spirit in the perpetrators. It seems to me, had I been in the crowd, I could have proposed something that would have been more full of fun, and decidedly less expensive to our parents."(26) In his personality and in his writing, King matured greatly at Dickinson. He would deeply miss male and female friends, faculty, campus buildings, and Carlisle. |

In his last entry before leaving Dickinson

with his diploma, King wrote a heart-felt reminiscence which encapsulates

his four years well:

With this entry, Horatio Collins King "entered the world" an intelligent, strong-willed and pleasant man. Three main forces can be credited for his success: family, friends, and Dickinson College. King was well educated because of his privileged background and because he used his opportunities productively. He went to a rigorous preparatory school, then Dickinson, studied law with the eminent Stanton, and later received masters and doctorate degrees. He was a passionate worker at nearly whatever he attempted, and was faithful to the people and organizations with which he affiliated. King grew most intellectually and emotionally at Dickinson where he was able to expand his interests and abilities. He learned public speaking by making recitations in his courses and orations in chapel. He learned leadership and organizing skills through his involvement with UPS and Phi Kappa Signma and his interactions with faculty and peers. Thus, numerous transformations occurred in his life because of his vast experiences at the college. He deserves to be remembered not only for what he did after Dickinson, but for what he did as a confused undergraduate searching out his way towards greatness.

The

segment of King's journal presented here covers the second session

of his sophomore year at Dickinson, from January to March 1856.(28)

He begins his journal for the new semester with a description of his winter

break spent in Washington, D.C.

|

|

Number

13

© 2000 Dickinson College. All rights reserved |